Of dogs, cats, baby chicks, mice and men

A Substack retrospective

For those who are new, have not been with me since the beginning (and beyond, going back to the early 1990s), or simply want a review, these are my top Substack posts by number of views.

Below them, I also share my top podcasts, a five-part history of the humane movement, and, even though they did not get as much traction, my favorite articles.

My most read post, “The Co-Optation of Austin Pets Alive,” is a cautionary tale about corruption and betrayal and explains how and why the No Kill movement was derailed by people willing to put animals in harm’s way for personal ambition.

Many shelters have made pandemic-era closures permanent, turning away volunteers, rescuers, families looking for lost animals, and adopters unless they make an appointment. My second most-read article, “The Growing Threat of Darkness,” explains why this reduces adoptions, reclaims, and rescues, increases killing, and leads to neglect and abuse.

From the first notes of Sarah McLachlan’s heartbreaking and haunting melody in the well-known ASPCA commercial, Americans nationwide brace themselves to be moved as their hearts and wallets open wide. That commercial alone has filled ASPCA coffers with tens of millions of dollars donated by animal lovers who believe that their generosity will be used to protect animals from harm because they are, in McLachlan’s words, “in the arms of an angel.” But for a little dog named Nyla and her rescuer, a young woman named Angel Hueca, the ASPCA would not live up to its lofty, though highly profitable, rhetoric. Like so many other animals before her, Nyla would find negligence, suffering, and death — a death whose heartbreak would be compounded for Angel by the cruelty she would subsequently suffer at the hands of callous, even emotionally abusive, ASPCA employees.

For a one-year-old dog at a Georgia pound, uncaring and incompetent staff botched what appears to be six attempts to inject her with a lethal dose of barbiturates before resorting to intracardiac injection — heartsticking her — a process that involves plunging a syringe through the chest wall and several layers of muscle into a dog’s heart. An animal killed by a heartstick feels extreme, severe pain (due to the amount of nerves) and then suffers a heart attack. To get to the heart, the needle would have to penetrate the skin, body wall with costal musculature, costal pleura, pleural cavity, pericardial pleura, fibrous pericardium, serous pericardium, pericardial cavity, epicardium, myocardium, endocardium, ventricular chamber, and if the lung is penetrated, the pulmonary pleura and lung tissue itself. It is so painful that Georgia law only allows it to be done when the dog is unconscious.

For all their discussion and professed concern regarding hierarchies of privilege, race and gender professors have proposed a prescription for human-animal relations that could not be more inequitable, uncharitable, and unkind. Indeed, they have called for the neglect, abuse, rape, and killing of animals — but only if the abuser is “queer,” “indigenous,” or a person of color. And some “animal protection” groups promote their books and modify policies accordingly.

Jonathan Franzen, the fiction author and self-proclaimed bird fanatic, has published a hit piece in The New Yorker, calling for the roundup of cats to protect so-called “native” birds. It rehashes arguments debunked in the 1990s and early aughts. It relies on other ideologues determined to kill cats, like the fanatics at PETA, who put to death 99% of cats. And it comes after universities, shelters, communities, health departments, and even states embraced a community cat sterilization program as an alternative to “catch and kill” because the evidence shows it is a good, humane, and effective policy — for cats, birds, and people; conclusions that the last three decades of experience have confirmed.

Laws that empower rescuers to save lives that “shelters” intend to kill are a no-cost way to reduce the number of animals who go out the back door in garbage bags. In California, Colorado, New York, and elsewhere, these “rescue access laws” were introduced to require shelters to notify rescuers before killing an animal. And given that such notifications are possible through shelter software already used by these facilities or available for free, complying would have required nothing more than a stroke on a keyboard. One click to let the rescuers know that a life needs saving. But, most of these laws failed to pass because of opposition. “Live and Let Die” explains how money and power from large, national groups combine to send “very friendly” animals who “love attention” and “love to be pet” to an early grave despite rescue groups ready, willing, and able to save them.

Human Animal Support Services (HASS) is a program urging “shelters” to make pandemic-era closures permanent by turning away stray animals. These policies manipulate intake and placement rates by abandoning the fundamental purpose — indeed the very definition — of a shelter: to provide a safety net of care for lost, homeless, and unwanted animals. Under HASS, “Intakes of healthy strays and owner surrenders doesn’t exist anymore,” and there is “No kennel space for rehoming, stray hold or intake.” Care for homeless and stray animals is left to chance: people who find animals are told to take them into their own homes until their families are located or leave them on the street. According to HASS, the “hope” is that the lost animal “finds its way back home.” Such hope is misplaced. For many animals, such policies are fatal.

At their national conference, The Humane Society of the United States held a workshop arguing that shelters should “start[ ] their own breeding programs” to meet public demand for puppies, a proposal Time magazine calls “a shocking idea, like a cocktail hour at rehab.” But it is more than “shocking.” It is a dangerous betrayal of animals:

Non-profit breeding operations will be just as cruel as for-profit commercial breeders, as many of them already are.

Shelters will be killing young, adult, and senior dogs in one part of the shelter while breeding dogs for sale in another.

It will derail hard-won progress in getting Americans to sterilize and adopt rather than breeding and buying.

It will undermine efforts to ban the sale of commercially bred animals in pet stores. Half a dozen states and hundreds of cities across the nation have already divested themselves from this pernicious harm, and as a result, half of all Nebraska’s puppy mills have shut down.

Puppy mills will also start breeding mixed-breed dogs. Indeed, nothing will stop puppy mills from incorporating as non-profits, calling themselves a “humane society” or rescue group, and selling puppies to the public as “adoptions.”

The ASPCA has succeeded in getting laws passed that create a new justification for killing animals — “mental suffering.” There is no definition of “mental suffering” or standards for applying it, despite that all animals can experience stress when entering a pound. Many are used to sleeping on beds and couches in homes or even living on the street and will find their familiar routines upended in a confined place that is loud, often dirty, unfamiliar, and disorienting. Getting them out of the shelter through adoption, foster, or rescue would end the stress, yet the new laws require none of these. It puts shy, scared, and traumatized animals at mortal risk.

Bowie, a shy 15-week-old puppy, was killed by the Los Angeles County pound, despite a rescue group willing to save him. AB 595, Bowie’s Law, was introduced to ensure that animals like him, who have a place to go, would be spared by requiring California shelters to notify rescuers 72 hours before killing an animal. But it was opposed by the National Animal Control Association, the ASPCA, Best Friends, and others. And because of that opposition, it died in the California Assembly and animals, like Bowie, continue to die needlessly along with it.

Here are the others who round out my most widely read and shared posts:

What would you do if you ran an animal protection organization with $776 million in annual revenue and $1.2 billion in assets? How much could you accomplish? The hypothetical is not far-fetched. Indeed, that amount of money is what only three organizations in the U.S. take in yearly and have in bank accounts.

What’s it like to be a dog being experimented on in a laboratory? A cat in the kill room of an animal “shelter”? A cow in a slaughterhouse? A mouse on a glue trap? A deer being hunted? A pig on a factory farm? I answer those questions using some of the latest findings in comparative neurobiology — the study of how different parts of the brain are connected.

Regardless of whether it is a billion-dollar company that profits from the abuse and killing of animals for food, a pound director who finds killing easier than doing the work necessary to stop it, an organization like PETA that rounds up to kill animals, a veterinary medical association trying to undermine lifesaving to maximize profits, or elected officials engaging in conduct that undermines our humane values, animal advocates cannot be intimidated into silence. Animals have no voice and need others to speak for them. Silencing people silences the animals. The First Amendment gives concerned citizens the protection they need to protect animals.

I’ve had many dogs in my life. I wear a dog tag with all their names, so they always stay close to my heart. Though Topham, one of my dogs, died in 2010, and Pickles, his brother, four years later, I occasionally dream about them and always wake up my wife when I do. “I saw the Boys,” I say. She always asks me how they are. I wrote this for Pickles on his 14th birthday, just a few months before he died.

Inspired by a visit to Greece and my 30-plus years doing cat rescue in the U.S., I look at what we owe cats (and their caretakers) who call our communities home. Specifically, it calls for embracing the Enlightenment values classical Greece bequeathed to the West, especially tolerance and kindness.

If you call a shelter (or wildlife facility) for assistance today, you would be hard-pressed to get them to send someone to come out and help an animal. Some of the more progressive shelters will sterilize a cat for free if you do the trapping and transporting, but they won’t go into the field to assist. Shelters are more reactive than proactive, and in the age of “community sheltering,” a euphemism for doing nothing, they might not even accept the animal for care and rehoming if you did all the other work. The organizations that raise the most money tend to be the most useless and regressive. When it comes to animal rescue, we are often on our own. So when I came across a squirrel with mange, I knew there was no one else to turn to. This is how I sprung into action.

I promoted the Do No Harm Act, model legislation I wrote for The No Kill Advocacy Center, which would make it illegal for anyone, including shelters and private veterinarians, to kill healthy and treatable animals. In response, a reader asked whether the ban on killing would apply to an otherwise healthy dog brought to a private veterinarian for “euthanasia” when the dog may be “aggressive.” Phrased another way, are the goals of protecting dogs and people mutually exclusive? Here is why they are not and why veterinarians should not be allowed to kill animals who are not irremediably suffering.

A successful shelter director I mentored contacted me about a job offer they received from one of the wealthy national organizations of which I have been critical. The director asked my advice about the costs vs. benefits of accepting the offer. It is not the first time I have received this kind of question. I have received a great many. My advice is always the same: don’t do it. Here’s why — and why no one listens, how they all come to regret their decision but ultimately go full dark side.

Here are my top podcasts:

While out for a walk with my dog Oswald, I came across several mice stuck on glue traps who had been dumped in a bag on the side of the road. Over two days, I would find a total of five mice. Two were dead; one was crying but had been sandwiched between two traps and had been partially stepped on, and he died shortly afterward. But two were still squirming, trying to get off, looking up at me. They were covered with poop and flies. I called Jennifer to come pick us up in the car. This is the story of how we painstakingly removed the mice from the glue traps, nursed them back to health, and then released them safely into the wild. It is also the story of how the experience almost broke our hearts and spirits, only to have millions of people redeem our faith in humanity.

Jennifer and I discuss how we often encounter animals needing rescue when we are running late, on vacation, or simply taking a wrong turn. Usually, it starts with one of us seeing something on the side of the road and asking, “What was that?” before turning the car around to do what we call the “double check.” We also discuss how rescuers can feel isolated in a world that seems indifferent to the suffering of our fellow earthlings, like when an animal clearly needs help but others don’t stop to offer it. Thankfully, our numbers are growing, and that is increasingly becoming rare. The conversation is fun and upbeat.

Here are two of my favorite articles, but they failed to get as much traction:

Winston Churchill once said that democracy was the worst form of government, except for all the others. Regarding economic systems, the same can be said of capitalism — at least for animals. While some romanticize Marxism by blaming capitalism for most societal ills, capitalism has no equal in lifting people — indeed, most of the world — out of poverty. In all of human history, things have never been better: “We’re living longer, richer lives with better access to clean water, education, electricity, and basic human rights than ever before.” Unfortunately, the opposite is true for most animals: “today is probably the worst period in time to be alive — especially for the species we’ve domesticated for food: chickens, pigs, cows, and increasingly, fish.” But while human prosperity has resulted in immense animal suffering, capitalism also holds the key to eliminating it.

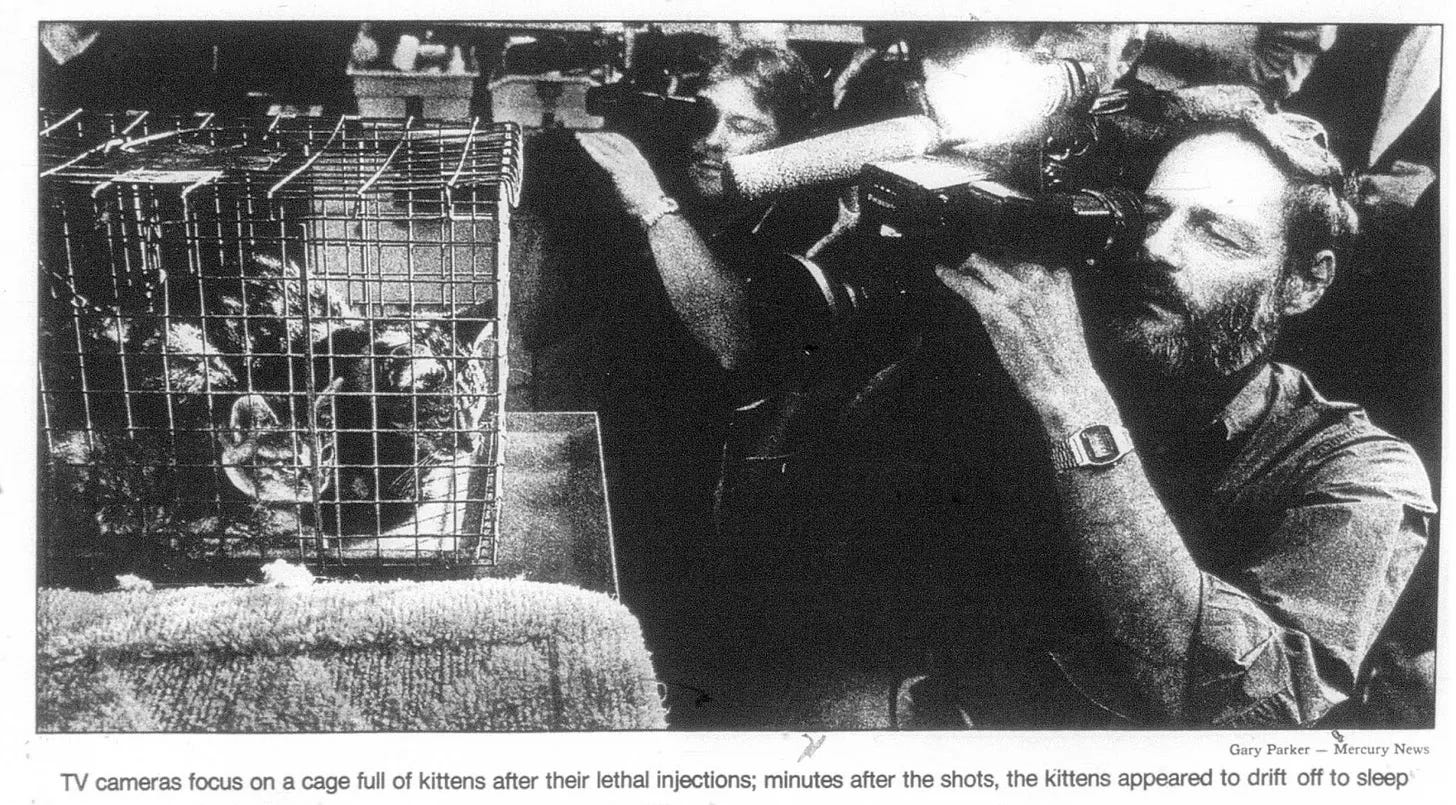

“The Status Revolution,” a new book by Chuck Thompson, claims the 1990 killing of puppies and kittens on national television by Kim Sturla, a shelter director, increased the status of rescued animals and launched the No Kill revolution in America. That makes no sense. You cannot kill your way to No Kill. And killing animals does not bestow status on them. It degrades them. To increase their status, one must show they matter by fighting for them and their right to live. While the credit for both belongs to someone else, Sturla leaves behind a legacy of failure, rejected ideas, and a horrific body count of animals for whom she showed a lifetime of disdain. Little wonder, The New York Times called the explanations given for trends in the book “scattershot” and “off the rails.” The conclusions in the chapter discussing dogs are even worse.

And, perhaps most important of all, here is my five-part series on the history of the humane movement, where we find ourselves right now, and my prescription for the future:

Part 1: Regarding Henry. The birth and betrayal of the humane movement in America.

In Part 1, we discuss the founding of our movement in the mid-19th century by Henry Bergh, who incorporated the first SPCA and how his vision of a society dedicated to animals — all animals — gave way to a network of humane societies that became the leading killers of dogs and cats in America. It was the movement's original sin and a great betrayal that reverberates today.

Part 2: A House of Cards Divided: The fight for the heart and soul of America’s animal shelters.

In Part 2, we discuss the internal battles that occurred throughout the 20th century between those who wanted to hold these organizations to a larger animal rights/animal protection mission — goals that included keeping animals in these pounds from ending up in laboratories to be experimented on — and those who viewed the animals in their pounds as a source of desired revenue. When Jennifer and I entered the movement in the 1990s, the regressive forces won. But there was hope, as one city recaptured its roots.

Part 3: All of Them: No Kill moves from the theoretical to the real.

In Part 3, we discuss how we moved our family from the San Francisco Bay Area to Western New York so that I could take over as director of an animal control shelter, creating the first No Kill community in the U.S. We discuss the subsequent founding of The No Kill Advocacy Center to replicate that success. Finally, we discuss the national No Kill Conference that brought together thousands of rescuers, volunteers, attorneys, directors, veterinarians, legislators, and reform activists nationwide. These efforts seeded the No Kill Equation model of sheltering — efforts that would result in the explosion of No Kill communities nationwide, saving millions of lives.

Part 4: A glass half full and half empty: we’ve made tremendous progress but we still have a long way to go.

In Part 4, we take stock of where we are now: deaths are at an all-time low, more people are turning to adoption and rescue, older animals in the twilight of their lives are the fastest-growing pet demographic in America, geriatric veterinary medicine is extending both the quantity and quality of pet lives and collectively we’re spending $100 billion every year on their care. That’s the good news. But, unfortunately, it is not the only news. As our movement has become more successful, it is also facing increasing threats from vested interests, corrupting influences, and pedestrian flaws of human nature.

Part 5: What’s Past is Prologue: To best serve animals, humane societies must recapture their roots.

There was a time when No Kill was just a hope. We dreamed it anyway. And because we did, it no longer is. We now have a solution to shelter killing that is not difficult, expensive, or beyond practical means to achieve. Unlike the “adopt some and kill the rest” form of animal sheltering that dominated our country for over a century, needlessly claiming the lives of millions of animals every year, there are now No Kill communities placing over 99% of all animals entrusted to their care. As we continue our work to make pound killing a thing of the past in every American community and then build upon that success to protect every animal, no matter the species, no matter the threat of harm, what will our map for the future look like? What roads will we take to do so? That is what we discuss in the fifth and final part.

Before Substack, I wrote articles for my website, the Huffington Post, a blogging platform, and elsewhere.

“This Week in Animal Protection,” my column, will return next week.

Thank you for everything you do for the non humans. I just wish more humans would open their hearts, eyes and minds to the horror of organizations like the 'humane society' and others who pretend to be helping animals. Thank you, Nathan Winograd, for all you do to help those who so few help. I have been rescuing dogs from the streets since 1984.

Thank you much, Nathan, for great retrospective and summary.