A Whole Lotta Bunk

“The Status Revolution,” a new book by Chuck Thompson, claims the 1990 killing of puppies and kittens on national television by Kim Sturla, a shelter director, increased the status of rescued animals and launched the No Kill revolution in America. That makes no sense. You cannot kill your way to No Kill. And killing animals does not bestow status on them. It degrades them. To increase their status, one must show they matter by fighting for them and their right to live. While the credit for both belongs to someone else, Sturla leaves behind a legacy of failure, rejected ideas, and a horrific body count of animals for whom she showed a lifetime of disdain for their safety, well-being, and rights. Little wonder, The New York Times called the explanations given for trends in the book “scattershot” and “off the rails.” The conclusions in the chapter discussing dogs are even worse.

Since the onset of the modern No Kill movement, a paradigm shift has occurred across the United States. In creating the environment that confers reputational success when a person makes the kind choice to adopt/rescue, the humane movement accomplished a tremendous feat: transforming animal companionship from a display of wealth and status via a dog’s pedigree into a demonstration of compassion and the recognition of the individuality and moral worth of dogs. What is now good for people — with adoption earning respect and admiration from peers — is also good for dogs as they are less likely to be killed in pounds or bred in the functional equivalent of factory farms. How did this happen?

The Status Revolution: The Improbable Story of How the Lowbrow Became the Highbrow, a new book by Chuck Thompson, purports to explain the transition. Unfortunately, he gets it horribly wrong. At the center of Thompson’s explanation and the hero of his revisionist account is Kim Sturla, who killed puppies on national television in 1990 as the director of the Peninsula Humane Society in San Mateo, California.

Although they are necessary to understand the absurdity of Thompson’s thesis, Thompson does not detail Sturla’s many failures. But I did in Redemption, my first book, and they are legion. Sturla oversaw an animal shelter that took in thousands of dogs and cats every year, most of whom she killed. Her record was hardly impressive. In fact, in that year alone, PHS put to death an astonishing 9,038 dogs and cats, over 75 percent of all cats the shelter took in. (The number is likely well over 10,000 because the agency failed to report the dogs and cats it killed ostensibly at the request of their “owners”).

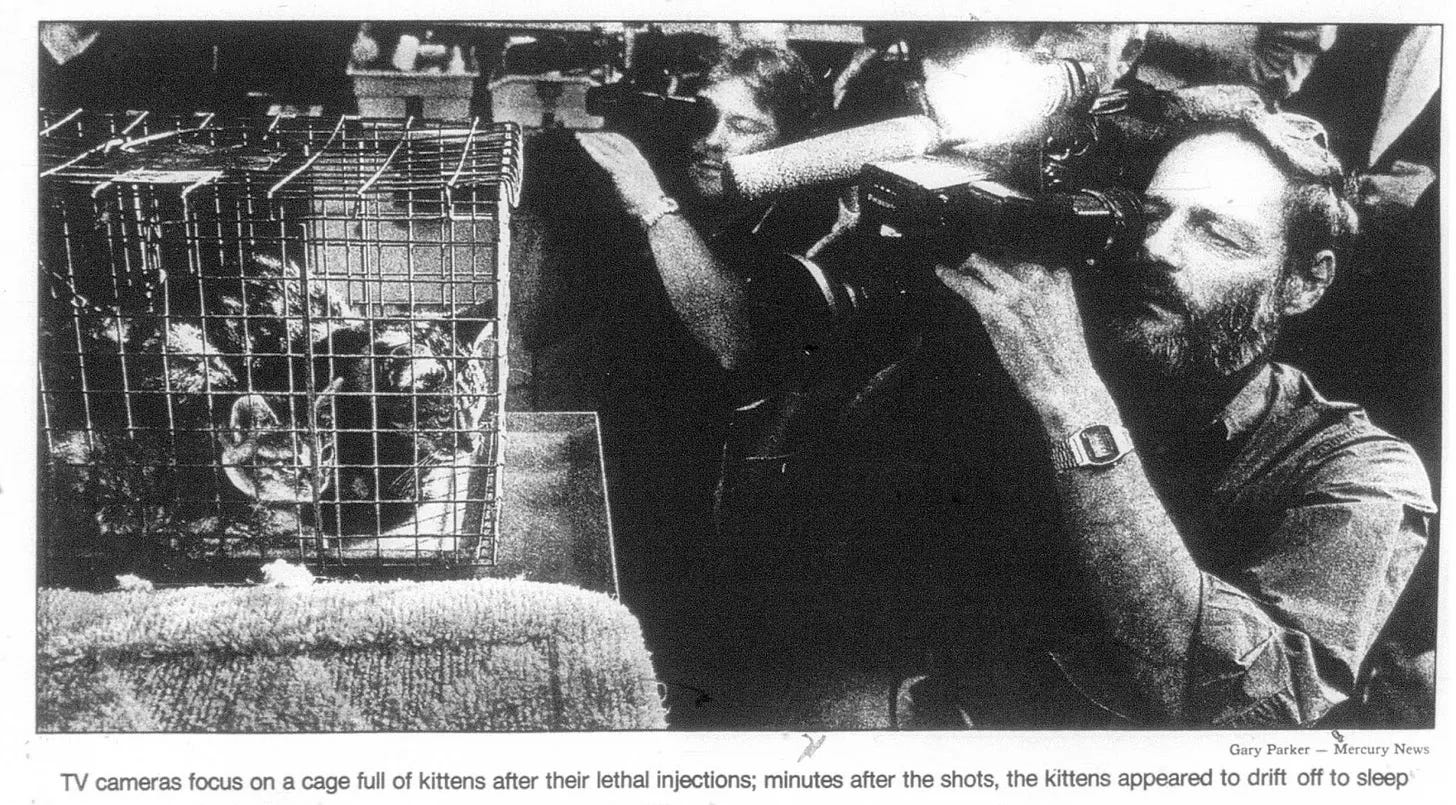

But on October 25, 1990, reporters from across the nation converged upon a small room in her shelter, and she had their full and rapt attention. While “cameras clicked and onlookers gasped,” Sturla took “a tan-and-gray calico cat and her four tiger-striped kittens” — all healthy, adoptable animals — “and injected them in the stomach with poison from a bottle marked ‘Fatal Plus.’” One by one, their tiny bodies went limp, and they slumped to the table. By the time she had finished, Sturla had killed eight animals, five cats and three dogs, on television. Dubbed a “public execution,” the first-of-its-kind public relations ploy was an instant sensation.

In Greensboro, North Carolina, Nevada City at the foothills of the Sierras and elsewhere, shelter directors likewise turned to killing healthy animals on television in hopes of shocking the public. Mitchell Fox, a shelter administrator in Seattle, Washington, put it bluntly:

We are killing animals every night at 6 o’clock behind closed doors, and we want very much to change that, to go public with it. We want to do this killing on the steps of city hall and in the parking lots of populated malls, and in parks. We want people to see it because there is nothing like that experience.

As one might expect from someone whose own organization killed upwards of 99% of animals it impounded — including (as we would later find out) stealing animals to kill, lying to people to acquire and kill their animals, and underreporting how much barbiturates it used to kill animals so it could kill other animals off the books — People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) applauded the move. “We’re hoping that this sort of approach is going to catch on,” a PETA spokesperson said.

Thompson credits Sturla and her ghastly P.R. gimmick with shifting how people viewed shelter animals. By killing them, he oxymoronically concludes, Sturla “brought prestige to a downtrodden group (stray dogs) while helping to make virtue signaling one of the new tenets of status.” That makes no sense.

Killing puppies and kittens is predicated upon the view that their lives are cheap and expendable, that taking their lives is of no moral consequence, and that they could and should be consigned to the garbage heap. Equally absurd, Sturla told Thompson she killed puppies and kittens on television because of her commitment to animal rights. Thompson credits her inspiration to do so with Tom Regan’s seminal 1986 book, The Case for Animal Rights. But Regan’s primary premise was that animals were entitled to the right to life, which Sturla did not believe in and openly violated every time she or her staff poisoned an animal to death in the “shelter” she managed. Indeed, Regan himself decried pound killing, arguing that “To persist in calling such practices ‘euthanizing animals’ is to wrap plain killing in a false verbal cover.” It is much more likely that Sturla, one of the No Kill movement’s most vociferous opponents, was motivated by a desire to punish the public. Indeed, the tagline for her campaign was that killing animals “is one Hell of a job. And we couldn’t do it without you.”

According to Chuck Thompson, however, Sturla had no choice:

[E]very ingredient for a community supportive of animal welfare issues was in place — well-off, pet-loving people with yards who readily attached themselves to progressive causes. Yet no appeal PHS made on behalf of its beleaguered shelter animals could persuade its affluent, bleeding-heart neighbors to adopt a pet.

Despite growing public awareness of animal welfare issues, humane societies and animal shelters across the country were banging their heads against the same walls, running the same gratuitous spay and neuter campaigns, failing to move the needle.

Lots of dogs. Lots of dog lovers. Little community response.

It wasn’t true.

Like Sturla and the shelter bureaucrats who mimicked her, Thompson (who had benefited from 30 years of history since then) failed to do his homework. He failed to ask the essential question: Did she have to kill these animals in the first place? But, once again, I did. In fact, that is the central question I asked in Redemption, and the answer is that she did not.

Physician, heal thyself

A short, roughly 20-minute drive north from PHS is The San Francisco SPCA (SF/SPCA), one of the nation’s oldest humane societies and the first west of the Rockies. At the time Sturla was insisting that she could do nothing to get people to adopt, requiring her to fill barrel after barrel with furry bodies, SF/SPCA Director Richard Avanzino was not so quietly upending “catch and kill” sheltering by implementing innovative programs to reduce birthrates, increase adoptions, save feral cats, and keep animals with their responsible caretakers. His philosophy was based on a simple belief — that people care what happens to lost and stray animals — and an equally simple idea — make it easy for people to do the right thing, and they will.

All told, Avanzino would pioneer a series of programs and services that have come to be called the No Kill Equation for their ability to enable any shelter in any community to end the killing of healthy and treatable animals. These programs included a behavior helpline to overcome the challenges people were facing which might cause them to give up on an animal, foster care, free sterilization, being open seven days a week and every evening so that working people and families with children could adopt, subsidized veterinary care, and so much more.

Like most shelters, for example, The SF/SPCA was built in an industrial part of the city away from where people live, work, and play. Instead of waiting for people to come to the shelter, Avanzino took the animals to them by launching the nation’s first offsite adoption program. He filled several vans with dogs and cats and set up temporary adoption booths throughout the city. In its heyday, there were seven offsite adoption locations in San Francisco, seven days a week.

This also allowed people to adopt animals without going into the shelter, which most people felt intimidated doing, fearing that the shelter would kill the animal they did not choose. By making the shelter safe for animals and by treating people as partners rather than enemies, Avanzino also made shelters safe for animal lovers.

These innovations combined to create the then-safest urban city for homeless dogs and cats in the United States, with a rate of killing that was a fraction of the national average and over 30 times less than communities with the highest death rates. The results proved that once an animal enters the threshold of a shelter, what happens to that animal is up to the shelter because there is enough love and compassion in any community to overcome the irresponsibility of the few. In short, shelter killing is a choice. On a national scale, they also inspired a revolution in sheltering.

I would work for Avanzino at The San Francisco SPCA before ultimately taking the model he created to an open-admission animal control facility in New York, surpassing San Francisco’s achievement and creating the first No Kill community by placing all but irremediably suffering animals. It didn’t matter if the animals were young, old, sick, injured, unweaned, or traumatized. They were all guaranteed a home, and they all found one. And we did it, not just for dogs and cats but also for rabbits, hamsters, gerbils, and every other species of sheltered animal. This achievement has since been replicated across the country by others. Collectively, these accomplishments have helped lead to a decline in killing nationwide by over 90%. It has been called “the single biggest success of the modern animal protection movement.”

Accordingly, it was not Kim Sturla in San Mateo and over half a dozen dead animals she executed on television that marked a turning point in the ascent of rescued dogs. That feat was accomplished despite her. The real hero of this story was Richard Avanzino, in San Francisco, and it was inspired by one dog named Sido he fought to save.

Saving Sido

According to the San Francisco Chronicle,

When Sido’s owner, San Francisco’s Mary Murphy, committed suicide in 1979, her will left strict instructions that Sido be taken to her veterinarian and “destroyed.” The will’s executor, Rebecca Wells Smith, said Murphy was afraid no one could take the right kind of care of her dog.

But Sido was in the care of the San Francisco SPCA, and its director, Richard Avanzino, saw things very differently. When Smith went to court to force the agency to have the dog killed, Avanzino refused, vowing that all the SPCA’s resources would be used to fight for her life.

“The law says a pet can be destroyed like a piece of furniture,” he told the Anchorage Daily News. “We’re saying that’s wrong.”

Ultimately, Avanzino would succeed in court: the judge hearing the case ruled that “the right to dispose of property after death does not extend to killing a living creature.” He would succeed in the state capital: the California legislature passed a law prohibiting killing an animal in a will. And he would succeed in the shelter: “Sido’s story told him the time was right to make the move from using death as a method of dealing with homeless animals, and calling that ‘humane.’”

“I knew then the American people were ready for a transition,” he told the Chronicle. As such,

If the no-kill movement has found its inspiration in what happened in San Francisco, it’s a legacy that movement owes to Sido, and her impact on Richard Avanzino. Saving Sido ‘was the turning point,’ he [said]. ‘Death is not a kindness. Animals, as our best friends, deserve more than an easing into the next world.’

It wasn’t so much that Avanzino changed hearts and minds. People already cared deeply about animals. He just made it easier for them to express that love. While directors like Sturla were intent on punishing people with public spectacles like killing dogs and cats on television or, as we will see below, passing punitive legislation, Avanzino stopped getting in their way, asked for their help, and created the environment that allowed them to do so.

And at the heart of Avanzino’s new approach to sheltering was a revolutionary and unprecedented insight that stood in stark contrast to Sturla’s deadly misanthropy: that it was the people inside our shelters, not the animal-loving public, that held the welfare and status of animals in low regard. By creating shelters that reflected, rather than hindered, the American public’s humane values, Avanzino believed we could transform sheltering across the United States. In short, while Sturla blamed the public for the killing, Avanzino saw people as the key to ending it.

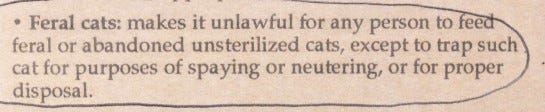

But Sturla remained unmoved. She failed to implement most of these programs and, in many cases, actively fought them. In addition to killing animals in San Mateo, while Avanzino was saving them less than 15 miles away in San Francisco, she continued to fight Avanzino’s efforts long after she left PHS. At The Fund for Animals, Sturla promoted state laws and local ordinances that would have made it illegal to feed community (feral) cats except, for example, to trap them — in her words — “for proper disposal,” as if they were nothing more than yesterday’s garbage. One of these proposed laws sought to make it illegal for community cats to be outdoors in California (AB 302). A companion bill (AB 1000) would have empowered animal control officers to kill cats in the “field” if they were not wearing a rabies tag. Had she succeeded, the outcome would have been a bloodbath, despite the fact there had not been a case of cat-to-human rabies transmission in the U.S. in over 30 years and none in California.

Thankfully, Sturla’s legislation failed after a broad-based coalition of cat caretakers, rescuers, No Kill advocates, and other cat lovers banded together to defeat them. As one of the executive committee members of that coalition, I was part of the team that descended on our state capitol and succeeded in getting the bills pulled from consideration.

A lack of self-reflection

With the passage of so much time, watching the widespread rejection of all she believed in, including the killing of healthy animals, and the widespread acceptance of all the programs she once rejected but which are responsible for both the meteoric decline in the national death rate and making the rescued animal the preferred dog of Americans, one would think that she would feel some measure of remorse. At the very least, one would expect her to express humility by declining to take credit for the success of others. Yet, over 30 years later, Sturla instead remains unrepentant. Worse, she doubles down on a legacy of failure, rejected ideas, and a horrific body count of animals for whom she showed a lifetime of disdain for their safety, well-being, and rights. It is a sad coda for Sturla, now in her 70s, on which to retire from a movement she claimed to be a part of, but never actually understood or clearly felt in her heart.

Although disappointing, I do not find it surprising. Many years ago, after a presentation that Sturla gave peddling disproved ideologies, when it was Avanzino’s turn at the podium, he opened his rebuttal by telling the audience: “Everything you just heard was a whole lotta bunk.”

And it is bunk. It does not take the proverbial rocket scientist to figure out that killing animals does not bestow status on them. It degrades them. To increase their status, one must show they matter by fighting for them and their right to live. That is how Avanzino and those who emulated his approach helped shift perceptions of animal shelters and the animals inside them. The question remains, however: How could Thompson have gotten it so wrong?

The answer is Thompson’s pessimistic view of human nature. Thompson does not view people’s commitment to rescued animals as genuine. It is, he argues, “virtue signaling.” To Thompson, people are incapable of benign motives and noble impulses. But if that were true, Sturla’s needless and cruel public execution would not have hurt people or led them to adopt, undermining his central thesis: how could one attempt to shock a conscience that did not exist?

Even if they did adopt, they would give up their dogs in droves at the first sign of incompatibility with their selfish interests. Instead, they spend $100 billion on them yearly and go to great lengths to ensure their health and happiness. And because people are keeping them for life, the senior animal is the fastest growing segment of the pet population, spawning the field of geriatric veterinary medicine, with specialized care and new treatments to keep them alive longer and as comfortably as possible. But since Thompson does not appear to have a language for progress, it is hardly surprising that he is blind to people’s great love for dogs and desire to do right by them. And that is why Avanzino’s quip about Sturla’s presentation can also be said of Thompson’s book.

I'm at a complete loss as to how these people set themselves up as animal advocates-worse are the people who buy into their bs. Sturla is a revolting human being who probably cannot afford to understand who she actually is and what she has done.

I was fortunate to be able to attend one of the first No-Kill conferences (1998 or 1999 in Concord, California) ,now called No More Homeless Pets conferneces), where I heard Richard Avanzino and Nathan Winograd speak. I also toured San Francisco SPCA during that trip) I think it was 1998, and the following year, in 1999, I spent a week at Best Friends Animal Sancuary, the largest no-kill animal sanctuary in the world. These experiences and the individuals I met showed me what can be achieved to improve and save the lives of animals.