The Best and Worst of Times

Human prosperity has resulted in immense animal suffering. It also holds the key to eliminating it.

A twisted symbiosis

Winston Churchill once said that democracy was the worst form of government, except for all the others. In terms of economic systems, the same can be said of capitalism — at least for animals. While some romanticize Marxism by blaming capitalism for most societal ills, capitalism has no equal in lifting people — indeed, most of the world — out of poverty. In all of human history, things have never been better: “We’re living longer, richer lives with better access to clean water, education, electricity, and basic human rights than ever before.”

Unfortunately, the opposite is true for most animals: “today is probably the worst period in time to be alive — especially for the species we’ve domesticated for food: chickens, pigs, cows, and increasingly, fish.” And it is no coincidence:

Human prosperity and animal suffering exist in a kind of twisted symbiosis: Economic growth leads to more food production and consumption, which in turn results in faster population growth and longer life expectancy, which then requires more intensive, factory-farmed meat to satiate growing populations.

Around 74 billion land animals are raised and killed for food. That’s a staggering number, but it pales in comparison to the number of fish killed for food each year: about one trillion, of which more than half now come from aquatic factory farms. In terms of sheer numbers and brutal conditions, raising and killing animals for food represents the greatest cause of human-induced suffering on the planet.

From the moment they are born to the moment they are killed, most animals raised for food will experience lives of unremitting torment. They will not know contentment, safety, happiness, or kindness. Instead, they will live short lives characterized by inescapable discomfort, social deprivation, and constant stress, all punctuated by moments of pain, fear, and, eventually, a brutal and untimely death.

“An exception to this rule — that human flourishing has come at the cost of animal welfare — is pets; US euthanasia rates at pet shelters have plummeted since the 1970s.” It wasn’t always the case: factories worked dogs to death, and pounds killed about 13.5 million dogs and cats yearly. But since the advent of humane alternatives — automation and sterilization — and more recent innovations in sheltering that replace killing — the No Kill Equation — a decoupling between human prosperity and animal suffering is taking place.

While we see this primarily in the area of animal companions, there is hope for other species, too. For example, residents of countries with advanced economies are reducing the number of their fellow earthlings they eat. “Over the last decade, Germany’s per-capita meat consumption fell 12.3 percent,” driven partly by advances in plant-based meats that look the same, taste the same, and are available at the same places as their animal-based counterparts. As sales of plant-based meats have doubled in those countries and will more than triple worldwide by 2030, consumption of meat from once-living animals is declining proportionally.

What came first: (concern for) the chicken or the (plant-based) egg?

It is tempting to think an evolving morality is to credit. As societies lift out of poverty and scarcity is overcome, people move up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, from survival (satisfying their biological needs for food, water, shelter, and safety) to self-actualization, which can include a greater concern for both people and animals. Historically, this has expressed itself through a small group of individuals challenging prevailing ethical mores. Unfortunately, those willing to do what is right when difficult or inconvenient tend to be and stay a small minority.

Most people, for example, claim to love animals and be concerned about the environment. Yet, most people still eat animals even though trillions of animals are not only abused and killed to do so, but it is the leading cause of deforestation, habitat destruction, and climate change. In other words, the factual and ethical case for veganism hasn’t changed the behavior of the vast majority of people. However, as we see in Germany and elsewhere, the increasing availability of convenient alternatives does. Make it easy for people to do the right thing, and they will.

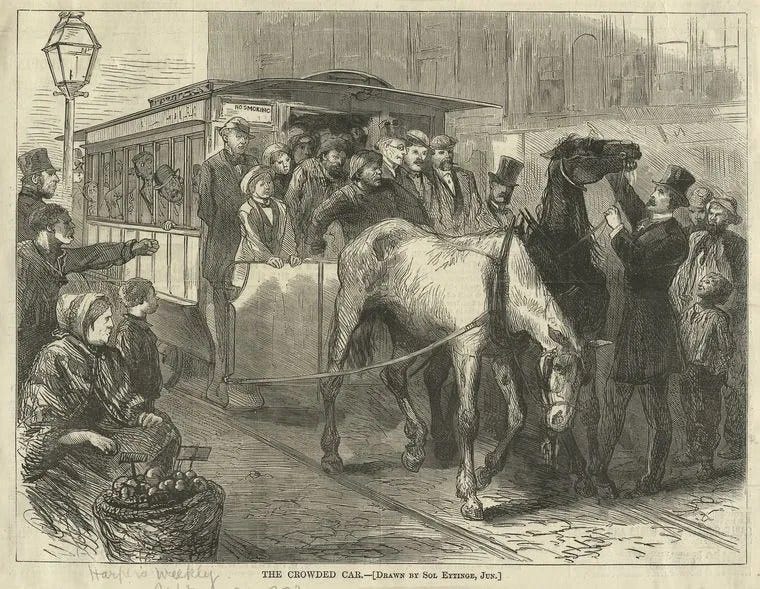

For example, dogs in 19th-century American cities were rounded up and brutally killed every summer by drowning, shooting, and being beaten to death in public squares. This cruelty resulted from a fear of “hydrophobia” (rabies), which people falsely believed was more prevalent and contagious during the summer. Rabies was rare, but

This convulsive disease, transmitted by the bite of a mad dog, was in those days widely dreaded and completely uncontrolled. Cases of [rabies] were relatively few, but the agony of the disease was so terrible, and death… inevitable, that the danger of mad dogs whipped the public into a hysteria of apprehension.

Although Henry Bergh, the founder of the nation’s first Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA), did a painstaking precinct-by-precinct search of New York City records, finding only one possible case of human rabies, which was not attributable to a dog bite, elected aldermen and their constituents were undeterred. While Bergh and his contemporaries in other cities lobbied to end these spectacles of cruelty, what finally brought them to an end and changed people’s view of their (im)morality was not ethical or even factual arguments, but Louis Pasteur’s creation of the rabies vaccine. The vaccine provided a humane alternative, and people embraced it.

Likewise, what ended the horse-drawn carriage was the creation of more humane modes of local transportation: cars and trolleys. Of course, ethics sometimes drives the creation of alternatives. The cruelty associated with horse-drawn trolleys led a friend and contemporary of Bergh’s to build the “horseless trolley,” what today, we call the cable car. Concern about the plight of animals killed for food also drives the founders of today’s start-ups looking to cultivate (“lab-grown”) chicken, beef, and fish from stem cells using bioreactors and precision fermentation.1 And these companies “say they have products ready to go.”

But President Joe Biden did not issue an executive order directing the Secretary of Agriculture, who oversees the country’s food supply, to “expand market opportunities for bioenergy and biobased products and services” because he loves cows. Instead, “meat grown without animal slaughter is on the cusp of being legally sold and eaten in the US” for the same reason as companies like Tyson support it: it cuts costs, increases profits, and opens up new market opportunities. Cultivated chicken, beef, and fish will allow Agri-business to close the breeding facilities, factory farms, and slaughterhouses. It will eliminate the mass of employees needed to raise and kill animals. And it will sideline the fleets of trucks necessary to transport animals from the hatcheries to the warehouses and from there, to their deaths.

Likewise, “scientists have developed a cancer drug without testing it on animals. The “researchers created a chip containing human tissue with microscopic sensors to precisely monitor the response of the human body — kidney, liver and heart — to specific drug treatments.” Although it spares the lives of animals, driving the technology is its efficiency: it is both more accurate and more profitable. A study looked at testing on 261 chemicals and found that the companies saved upwards of $70,000,000 by using technology rather than animals. (Testing also spared 150,000 animals). Armed with those findings, the U.S. Senate unanimously passed S.2952, the FDA Modernization Act. The bill removes the requirement that drugs “be tested on animals before they could be used on humans in clinical trials.” Instead, the bill “gives drug sponsors the option to use scientifically rigorous, proven non-animal test methods,” including cell-based assays, organ chips, computer models, and other non-animal or human biology-based test methods. As the saying goes, “Build a better mousetrap, and the world beats a path to your door.”

Decoupling animal harm from human prosperity

While morality can sometimes spur the creation and adoption of the alternative more quickly, it is not a prerequisite to either. But market economies may be. And of all the market economies, capitalism — with its relentless pursuit of innovation to lower costs and increase profitability — promotes alternative technologies in ways that other economic (and political systems like communism) do not. As such, it is the cause and the potential cure for so much animal suffering.

While capitalism is often criticized as driving consumerism at the expense of values, such a view ignores the more profound way capitalism often comes to create values through the creation of alternatives. All economic systems are built on consumerism. That is how people in societies of 330 million (in the case of the U.S.) or 1.4 billion (in the case of China and India) acquire the resources needed to survive: food, clothes, housing, transportation, and other products, programs, and services.

The difference is that consumerism isn’t driven by efficiency and cannot be influenced in a more humane direction in a communist country in the same way as in a democratic-capitalist one. In the latter, somebody who creates an alternative to products or services that harm animals (a clay pigeon, a cable car, a synthetic alternative to an animal-based product) can move humanity toward more humane practices and thus alter their moral calculus about the animal-based product it replaced.

In a communist society, that may not be possible. For example, China’s “medicinal” animal husbandry industry — factory farming animals so that their tissues, organs, and secretions can be used for Chinese “medicine” — is a close second to factory farming animals for food in terms of sheer brutality. This includes harvesting bear bile in some of the cruelest conditions imaginable, drinking goose and chicken blood from live animals, and skinning deer and donkeys alive (ostensibly to improve the medicinal quality). But unlike raising animals for food, it is brutality for brutality’s sake because the “medicines” don't work and are not intended to. They are a jobs program created and promoted as “miracle cures” under Chairman Mao Zedong to keep people in communist bondage. The industry provides jobs for unskilled, uneducated peasant farmers and promises “prestige” careers in “medicine” for equally uneducated laborers in cities.

Consequently, despite synthetic versions of bear bile, these are not being adopted widely because bear bile and other animal-based “medicines” are claimed to be “ancient wisdom” and “traditional” Chinese cultural practices rather than Western imports (though they are neither ancient nor Chinese, having been imported from the equally backward Soviet Union). Under communism, criticizing Chinese “medicine” is criticizing the state.

Regardless of whether they are concerned about the plight of people, the plight of animals, or both, the only people who still take communism seriously are people who are anything but: naive young people ignorant of history and academics seeking to make a name for themselves, by positing “theories” irrespective of communism’s repeated history of brutality and, ultimately, failure.2

By contrast, to the extent that capitalism’s success at getting people out of poverty results in more animal harm, its continued success through technological advancement will also soon liberate them from bondage, in ways that bears tortured for their bile in a communist state will not. In other words, once a capitalist economy becomes advanced, the “twisted symbiosis” between human prosperity and animal harm tends to decouple.

Capitalism’s ethical underpinning

This is not a plea for unfettered capitalism. Capitalism has its blind spots. One of those is that it views everything as commodities, including animals. When animals are considered mere commodities, as in factory farms, on race tracks, or in breeding mills, they suffer: where there is a profit to be made on the backs of animals, those backs are strained and often broken. But it is naive to look toward Marxism as the antidote. Instead, we must strike a balance between the extremes of laissez-faire and a command economy.

After a humane alternative replaces animal harm and societal morality shifts — such as rescue and adoption to replace breeding dogs and other animals for the pet trade — democracy provides the mechanism to take animals out of the marketplace. Unlike communism, democracy provides the freedom of speech and public participation necessary to influence people and policymakers to embrace the ethical alternative and outlaw traditional harm, such as laws banning the retail sale of commercially-bred animals in pet stores, but allowing those pet stores to offer animals for adoption by partnering with rescue groups or shelters.

We spend much of our focus in the animal rights movement trying to philosophically convert people to our cause, including veganism. These efforts are an essential part of our movement’s advocacy because they can inspire alternatives, and once those exist, they can get people to embrace them more quickly. They also take animals out of the market.3 Still, they are not enough because they do not seek to eliminate the most significant roadblock preventing more people from acting as we want them to: the inherited infrastructure that makes it hard, rather than easy, for people to do the right thing. As Henry Bergh and his contemporaries learned the hard way, focusing on the ethics before the alternative is often putting the cart before the horse, and that is a difficult undertaking when your cart and your horse have such a long way to go.

The great German physicist Max Planck once noted,

A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.

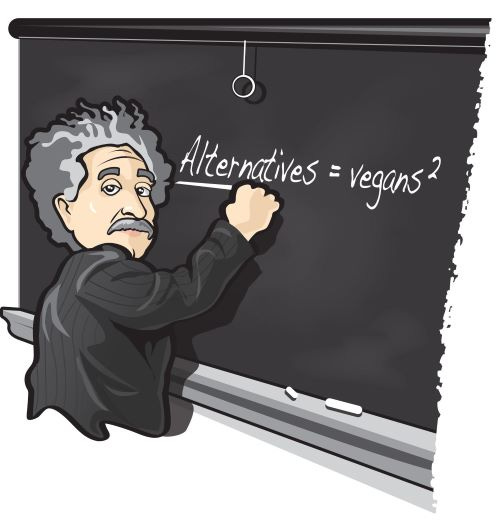

A corollary to Planck’s aphorism is that reducing animal cruelty is not necessarily driven by ethics but by creating humane alternatives. Or as Jennifer, my wife, and I argued over a decade ago in All American Vegan, our cookbook: the number of meat alternatives equals the number of vegans squared.

These changes and others, like drug testing, and the luxury car industry’s move to replace leather with synthetics, will not just revolutionize — and spare — the lives of billions of animals every year; they will realign the relationship with our fellow earthlings. When people no longer have to justify harm because of their own choices, they will be less likely to put up with the justifications others make to harm animals. Alternatives will have shifted their “morality.”

Cultivated meat is made from a one-time draw of stem cells. The stem cells are then replicated in a laboratory and grown in an animal-free medium to produce real meat from animals without killing.

As historian Scott Anderson writes,

Quite aside from its utopian pretensions in theory, what communism had displayed time and again in practice was a system tailor-made for the most cunning or vicious or depraved to prosper. Amind the blood-drenched history of the twentieth century, just two communist leaders — Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong — had, through a combination of purges and criminally incompetent economic experiments, killed off an estimated sixty million of their own countrymen. If you added the lesser lights of the communist world, its Pol Pots and Kim Il-sungs and Haile Mengistus, one could easily add another ten or fifteen million to the body count. Given this gruesome track record, shouldn't any right-thinking person be anti-communist in the same way they should be anti-Nazi or anti-child molester or anti-polio?

In addition to capitalism and democracy, promoting human and animal flourishing requires the embrace of Enlightenment values, starting with the unalienable rights to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” While the revolutionary war they sparked may be over, the battles for liberation they inspired are not. The last two centuries have witnessed one disenfranchised group after another build on their foundation to win equal rights and equal protection under the law.

By exposing the hypocrisy that one group’s rights were regarded as “self-evident,” while others were not acknowledged at all, abolitionists, suffragists, civil rights activists, and disabled rights advocates have all invoked the Declaration of Independence and the eternal principles it espouses in their own quest to realize its promises and help us to form a more perfect union.

And yet there are still billions of beings who do not yet have the rights we demand and accept as “unalienable” for ourselves. There are still billions of beings who — though they may differ from us in some ways — share the things which, as the Declaration proclaims, are the things that matter most: the desire to live, to be free, and to be happy. In these significant ways, humans and non-human animals are identical. Aren’t they entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness? Of course, they are.

Well written and researched. Thought provoking. An apothegm I created, "Tradition Ends Where Cruelty Begins," which I commonly use in response to bull fighting and fox hunting, comes to mind in respect to Chinese "medicine." Nice work!

Very enlightening -- so many great points -- thank you -- definitely will share and share