“Someone ought to do something”

When it comes to rescuing an animal in distress, that someone is YOU

This is an uplifting story of how I helped a squirrel in my neighborhood suffering from mange. But first, some context…

In the late ‘90s, Treasure Island, the former Navy base off the shore of San Francisco, was home to a large number of feral cats, especially in and around the barracks. The cats were abandoned — or the offspring of cats who were abandoned — by Navy personnel when they shipped out. The San Francisco SPCA, which back then represented the vanguard of the No Kill movement (it is now a staunch defender of killing), had negotiated the first-ever TNR program on a military base.

Army (of Compassion) vs. Navy (Cats)

With the Navy having turned Treasure Island over to the City of San Francisco and high-end retail and condominium plans underway, the cats had to be relocated as the barracks, which had fallen into disrepair, were getting bulldozed.

At the time, I headed the San Francisco SPCA department that oversaw the feral cat program, and we swung into action. Deploying our army of compassion, the caretakers we worked with re-trapped and moved the cats. But, like cats in general, some were obstinate. Wary from having been caught once to get sterilized, they avoided the traps — and the City’s deadline was approaching.1 So my team and I hired a contractor to build and install one-way doors in the former vent holes that allowed the cats to go in and out under the barracks, and then teams of us — myself included — went under the barracks, which were enormous, to make sure they were free of kittens and sweep them empty of cats.

It wasn’t the only time we went out in the field. I’d also send a team to trap cats, transport them to our clinic for surgery, and then return them in more run-of-the-mill situations, such as an elderly feeder asking us for help.

Fast forward some 25 years, if you call a shelter for assistance today, you would be hard-pressed to get them to send someone to come out and help an animal. Some of the more progressive shelters will sterilize a cat for free if you do the trapping and transporting, but they won’t go into the field to assist. Shelters are more reactive than proactive, and in the age of “community sheltering,” a euphemism for doing nothing, they might not even accept the animal for care and rehoming if you did all the other work. The organizations that raise the most money tend to be the most useless and regressive. When it comes to animal rescue, we are often on our own.

No one is coming

Wildlife rescue is no different. When we found a pigeon with a broken wing who had been hit by a car, the only assistance the local wildlife rehabilitation hospital would offer us was to kill him. That was 15 years ago, and Commander Seymour Higgins still lives with us.

More recently, my wife saw what looked like a sick, skinny, and somewhat wobbly bobcat sitting in the grass at a local park. The nearby wildlife hospital told us they would not send someone out to assess the situation, nor would they lend us a trap. We had to buy our own trap and trap the bobcat at our own risk, and if we were successful, we could bring the bobcat to them — but once there, what happened to him was entirely up to them. Again, two decades earlier, when I was in San Francisco, we routinely sent out a team to assess wildlife issues, formulate a plan, and take action to provide care and rehabilitation.

A mangy squirrel needed help

So when I recently encountered a squirrel losing his hair and covered in bloody and scabby wounds while walking my dog, I knew helping him was up to me. Admittedly, I tried a Hail Mary, reaching out to a wildlife rehabilitation hospital to see how they could assist or what kind of treatment I could give him.

I asked what they recommended, and I got the standard response — cue pedantic tone: that as a non-expert, I could not treat him, and they would not come to do it themselves. Instead, I was told to trap him and bring him there — and once there, what happened to him was up to them. If he were deemed a “native” squirrel, they would provide care. If he was considered “non-native” — wildlife rescue’s equivalent of a breed discriminatory policy — or his mange was especially difficult, they would kill him (as he was not part of a threatened species). Pass.

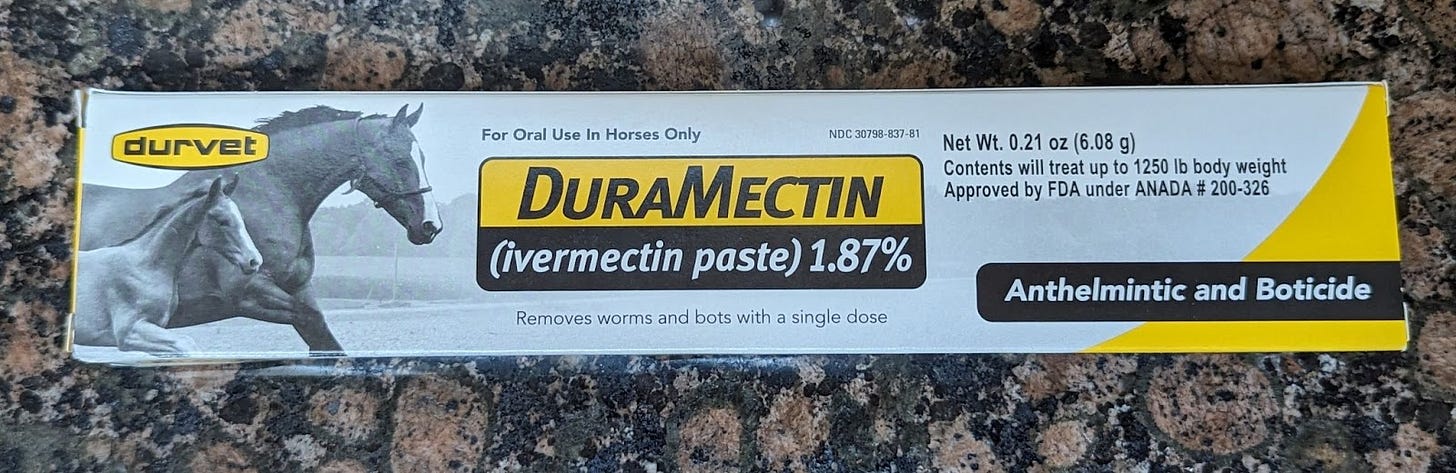

My research in squirrel chatrooms — yes, they exist — gave me a treatment regimen used by others with success: ivermectin, an anti-parasitic. Ivermectin plays an outsized role in America’s culture wars — having been brought to prominence by a subsection of the anti-vaccine crowd who claim it is a preventive or treatment for COVID. But, I was not interested in any of that and was happy to find out I could order it from Amazon without a prescription.

According to my fellow squirrel boosters, you coat a cashew or other nut in Ivermectin, let it sit overnight so it soaks in, and then give it to the squirrel. Ivermectin is a horse wormer, so a little goes a long way for a squirrel — no more than a grain of rice-sized amount. The treatment is given again one week later. Finally, the squirrel gets a third dose a week after that. Three treated cashews, each with a grain-sized amount of ivermectin, over three weeks, each one week apart.

Week number 1; dose number 1

The next day, he was waiting for me, where I usually fed him a handful of peanuts and sunflower seeds. He looked terrible. In addition to losing more of his hair, he was covered in open bloody wounds. (Eventually, he would lose all of his hair.)

I took the ivermectin-coated cashew, which I kept in a cellophane-covered shot glass in my jacket pocket, set the cashew down on the fence near where he was waiting, and backed away. As I retreated, he approached, sniffed the cashew, grabbed it, and ate it. Success!

I then fed him his usual breakfast and left.

Week number 2; dose number 2

I continued feeding him every day, but I did not see him after day four, and his second dose was due in three days. The morning of the seventh day, he did not come. I was discouraged.

About 6 pm that day, my wife and I were driving home from an errand when I took a detour to the usual spot where I fed him. Since it was early evening, not the morning, I was not very hopeful — but there he was!

Although all his hair was gone, the wounds had healed entirely — and for the first time since I came across him, he was not constantly scratching from the mites.

I exited the car and slowly approached with the second ivermectin-coated cashew in my pocket. I removed it from the shot glass, set it down, and walked away. He slowly approached, grabbed it, and climbed up a telephone pole to eat it. Dose number 2 was also a success! I fed him a handful of peanuts and sunflower seeds and left.

Almost week number 3; dose number 3

Again, I did not see him for several days, but on day four, he was waiting for me on the fence. I decided not to tempt fate and seized the opportunity. I gave him the third dose a couple of days early. He ate it.

Getting better all the time

Over the next 10-20 days, his hair began to grow back. First little by little, then all at once.

Always alone when he was mangy, he was now traveling in a little posse. I continued to see and feed him with the others he hung out with, and over time, his hair grew full, his body filled out from all the nuts, and he blended in with the rest of the squirrels.

I can no longer tell him apart.

Mission: Accomplished.

Typical of the City, the barracks would not get demolished for over a decade, but all the cats were gone.

Hi Nathan!

I so love the story of this little guy and your dedicated treatment plan to help him recover! He must be feeling so much better now and saying to himself, wow, those were great cashews! :-)

We actually do have some dedicated folks here in Vermont (I know several) at our local humane shelter, who go out and do what has to be done, in the field and at inconvenient hours/locations. But we're a small rural state and we do things differently here! You're right, it does work better when people actually get involved and don't try to pass things off to the next "official level".

Thank you as always for helping animals with your whole heart!!