Academia’s war on animals

Critical Race Theory professors defend abuse and call for the perpetrators to go free

As regular readers of my columns know, I have written numerous articles challenging professors who sacrifice the health, safety, and rights of animals to Critical Race Theory, Critical Gender Theory, and anti-capitalist/Marxist ideologies (collectively, CRT). This includes books and journal articles that:

Claim that viewing animals as family members, letting them sleep in the house, providing medical care, and showing affection are “white” values, while black people treat animals “as resources, whether protective (as in guarding) or financial (as in breeding or possibly fighting)”;

Criticize placing dogs who survived dogfighting in caring, family homes because “they were effectively segregated from Blackness”;

Call for more animals to be killed in pounds or left on the streets instead of placed in homes so as not to promote “settler-colonial and racist dynamics of land allocation”;

Call for permitting dogs to be left on chains 24 hours a day, seven days a week, if they belong to black, Latino, or other non-white people;

Call for humane societies to partner with dog fighters by providing free vaccinations for dogs who will be used as bait and ripped to shreds rather than rescuing the dogs and having the perpetrators arrested and prosecuted;

Promote defunding the police and releasing all prisoners convicted of animal neglect and abuse, even in cases of torture and killing, because abusers are “victims,” too;

Criticize the use of technology, like wheelchairs, to give disabled animals mobility, claiming it “erases” disabled people;

Advocate against rescuing and finding homes for disabled dogs because doing so stigmatizes disabled people by reinforcing “oppressive norms”;

Call for killing dogs in pounds instead of giving them “white” names because otherwise we’d be leaning into racism; and,

Advocate for “pansexual” relations with animals — the rape of dogs, horses, and others — in the name of “queering the human-animal bond.”

As I have repeatedly written, we should never confuse the racist tropes and cruel policies peddled by professors seeking to make a name for themselves in academia with the cause of animal protection or human dignity. They are not the same, and they never have been.

In the latest call to excuse violence towards animals, Kelly Montford, a professor who studies race, gender, poverty, and crime, Darren Chang, a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology, and Selingul Yalcin, a law student, decry efforts to take animal abuse seriously, including greater enforcement and more substantial penalties. To them, strong penalties for animal abuse and neglect, including felonizing torture and killing, specialized training for police to enforce animal welfare laws, and first-of-its-kind police department “animal cruelty investigation unit[s]” are not to be celebrated as progress.

In “Anti-Carceral Approaches to Addressing Harms Against Animals,” they instead call for “Restorative Justice,” a combination of defunding the police, abolishing prisons, anti-corporate and anti-capitalist activism, and roleplaying because enforcement of anti-cruelty laws is designed to protect the “heteronuclear white family,” support “racist and colonial legal institutions,” and expand the “carceral” state. They could not be more wrong.

One of the primary criticisms Montford and her colleagues levy against criminal enforcement is that the inability of impoverished or homeless people to meet their legal obligations should not be punished. I agree that some punitive approaches can be counterproductive, such as enforcing licensing laws, pet limit laws, leash laws, and similar animal control ordinances. Not only do they tend to be poor proxies for animal protection, they are often not about protection at all. This is an argument I made over a decade ago in my 2008 book Redemption and have made elsewhere since.

For example, studies show that people living in neighborhoods with high rates of poverty are “more likely to befriend stray or feral animals of unknown origin by occasionally feeding them or briefly letting them into their homes” and “consider to be unproblematic community pets or tolerate as just part of the neighborhood landscape.” By contrast, “animal control officers see them as nuisances to be disposed of, even though residents have not filed a complaint with the department and consider them to be shared community pets.” This not only sets up residents in an antagonistic relationship with animal services, it results in higher rates of killing because of the prohibitively high reclaim and citation fees charged by regressive pounds.

But animal cruelty laws do protect animals. And they do so by setting out minimum standards of care and proscribing conduct that falls below them. They criminalize animal mistreatment, not poverty, and contrary to Montford’s claims, they are not mutually exclusive with the “carrot.” Of course, there are times that education and subsidized services will achieve the desired outcome better than citations or incarceration, such as providing free fencing to get dogs off chains and quality food to get cats and dogs needed nutrition. We want behaviors to change in cases of neglect, through education and services if possible and when appropriate, but through prosecution if necessary because the welfare of animals is of consequence. Any argument to the contrary not only offers a false “either-or” choice, it throws the proverbial baby out with the bathwater.

Take the example they cite for their proposition. According to Montford, a police officer in Iowa City, IA,1 found Zeus — a dog belonging to Michael Beaver — tied up and in distress at a homeless camp.

Zeus was alone with a water bowl in extreme heat conditions and his owner, Beaver, was absent. At the veterinary hospital, Zeus’s health issues were so severe that he was euthanized. Beaver, who was later charged with and pled guilty to misdemeanor animal neglect, stated that he was aware Zeus was sick and attempted to have medical care provided for Zeus; however, he could not afford the $800 veterinary hospital bill.

Montford is not being honest. Montford writes that “Zeus was alone with a water bowl,” implying he had access to water. In fact, the water bowl was empty and the heat index was 111 degrees. To elicit sympathy for Beaver, she also neglected to note that Zeus had kidney disease — and that Beaver knew it — so water would have been especially crucial. When a dog’s kidneys are diseased, they cannot filter toxins from the blood as well as they should. To compensate, the body increases blood flow to the kidneys, producing more urine and requiring dogs to drink more water. Zeus died of renal failure precisely because he did not have access to water. The homeless camp was next to the Iowa River.

If Montford were honest, she would blame Beaver for Zeus’ suffering and death because it was his fault. Beaver is a grown man who failed to provide what Zeus needed and knowingly failed to protect him from harm. Indeed, he caused it. While states should provide veterinary and other services for free, as I have argued repeatedly elsewhere — and Montford later admits those services were available — a “failure to afford” defense to animal cruelty would subjugate the rights of animals to the interests of the people they are connected to and reaffirm their status as “property” which Montford decries as it relates to other animals, including animals raised and killed for food. In addition to his poverty, Montford says that Beaver should not have been prosecuted because he “depended on Zeus for emotional support,” but that, too, is an effort to subjugate Zeus’ health and safety to Beaver’s interest in “emotional support.” Zeus isn’t a “thing,” like a comfort blanket. She can’t have it both ways.

To try, Montford infantilizes Michael Beaver by removing any agency or culpability on his part. She is not alone in doing so. Other CRT proponents also stereotype and fetishize so-called “marginalized” people. For example, Professor Katja Guenther, who similarly studies “race and gender,” recounts the story of a Latino man who “dropped [his…] puppy while escaping from mall security officers on a bicycle after stealing a pair of Wrangler jeans.” To Guenther, it was his “status as marginalized” — as a Latino man — that explains the fate of the dog, not that he put the puppy in harm’s way while committing a crime. In yet another example, Guenther portrays the actions of a woman who was breeding a dog — a dog who died — as resulting from her “status as a poorly educated queer woman of color,” even though she was not only selling the puppies to buy drugs, but it was the dog who ended up dead. Guenther goes so far as to claim that when “marginalized” people mistreat a dog, they actually believe that they are doing what is best “within the constraints of their knowledge and resources, both of which are limited by the nexus of their class, status as immigrants, and ethnicity.” To Montford and others of her CRT ilk, white people think and do things; Black, Latino, and poor people and people with sexual paraphilias have things happen to them because they lack intellect and agency. It is racist, sexist, and classist, and it is contrary to the evidence.

For all the discussion and professed concern regarding hierarchies of privilege, Montford’s prescription for human-animal relations could not be more inequitable, uncharitable, and unkind. Were the movement to accept her premise that all animals do not bear the same rights and that all humans do not bear the same responsibilities to those animals, we would create a privileged class of animal abusers by subordinating the rights of animals to the interests of those who harm them, undermining the central tenet of the animal protection movement and leaving animals in danger. That is something we should never do.

Contradicting herself later, Montford lauds legal efforts to appoint guardians in cruelty cases because they acknowledge that animals have interests independent of the people they are connected to. But she then argues they should not be enforced because they exclude most animals, including hunted wild animals and animals raised and killed to be eaten. From the moment they are born to the moment their necks are slit, the vast majority of “farmed” animals will experience lives of unremitting torment. They will know neither contentment, respite, safety, happiness, or kindness. Instead, they will live a short life characterized by inescapable discomfort, social deprivation, the thwarting of every natural instinct, and constant stress, all punctuated by moments of pain, terror, and, eventually, an untimely and brutal death. Indeed, the exploitation, abuse, and killing of animals for food is the single greatest source of human-caused suffering on the planet, yet it is legal.

As normative and legal changes almost always involve tackling evils one at a time, thereby setting a precedent and reducing tolerance for animal cruelty, the obvious answer is to work to prohibit that conduct. Montford, however, would have us do the opposite: decriminalize the abuse of companion animals until all animals, including animals in laboratories, wild animals, and “farmed” animals, are likewise protected. That means “we would simply permit all manner of animal cruelty, on the theory that there is no principled distinction between what we currently permit and what we currently prohibit.” Not only would any progress for animals be impossible, but we’d also have to undo the progress we’ve already made.

But while Montford rightly accuses society of being selective about the animals they care about, she, too, is guilty of this. CRT academics have no problem with hunting wild animals or abusing animals who will be eaten, so long as those doing the hunting or abusing are “marginalized.” They have defended the harpooning of whales and clubbing of seals because of “native cosmologies.” They have claimed that animals want to die and do not mind suffering when they do if the hunter is “Indigenous.” They even apply dual standards when it comes to dogs, such as arguing against prosecuting abusers like Michael Vick, claiming black dog fighters are the real “victims.” To Montford, Zeus’ interests are entirely subordinate to those of Michael Beaver, the man responsible for his suffering and death. Again, she cannot have it both ways.

So what does Montford propose as an alternative to enforcement of cruelty laws? Montford advocates for roleplaying, where someone ostensibly pretends to be the animal or a veterinarian represents the interests of the animal and explains to the abuser “the physical and psychological impact of the harm experienced by the animal.” In addition to the fiction that a perpetrator doesn’t know the obvious and would not have done so had they known that being covered in gasoline and lit on fire hurts, Montford believes that Restorative Justice would also prevent the state from taking the animal away because, like women involved in domestic violence situations, “individuals involved in violent relationships might not want to leave these relationships, but do want the violence to end.” But that is how women continue to get battered until they end up dead, the same fate that awaits animals who are not taken into protective custody.

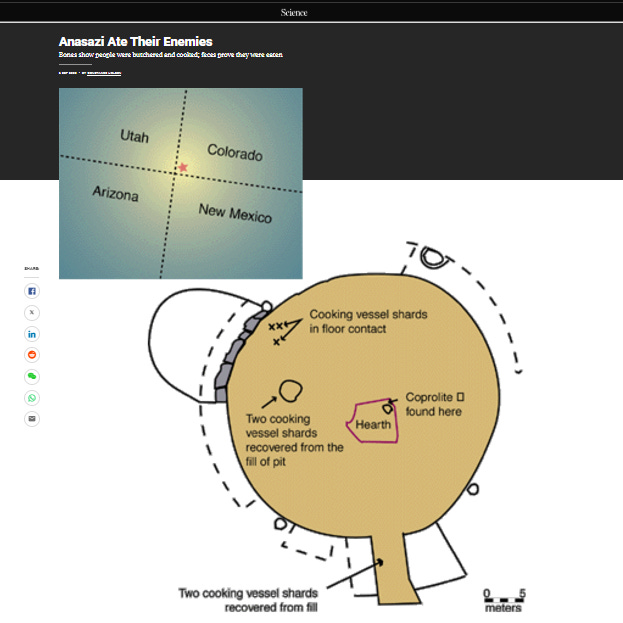

Despite this, Montford insists Restorative Justice is better because it is “modeled on Indigenous ways of responding to harm and rule-breaking,” as if that alone makes it worthy. But that makes no sense for many reasons, not the least of which is that there is no uniform “Indigenous” model. The practices of these disparate populations — some of which were homicidal cannibals forcing each other to live on the edges of dangerous cliffs to avoid becoming soup — have always been a patchwork collection of regional and even local cultures, often based on mythologies that changed over time.

Even the term “Indigenous” is a misnomer. Humans are not “native” to anywhere but the African continent. Calling people outside that continent “Indigenous” is not only factually inaccurate, it is laden with a morality that is undeserved. It wrongly suggests that anything they do is, by definition, the moral high ground because they are the ones doing it, even when animals are horrifically brutalized.

In the end, there is no real evidence that Restorative Justice works, but plenty of evidence that it doesn’t. I live in Oakland, California, ground zero regarding bad public policy resulting from these ideologies. At financial hardship, my wife and I recently spent thousands of dollars installing security measures to protect our family from the opportunistic criminals that now troll through the neighborhood, looking for packages, mail, cars, tools, and dogs to steal. As I recently learned when trying to find someone to give me an estimate, many contractors will no longer accept work here.

In 2023, the Oakland Police Department reported that “only 3 percent of violent crimes resulted in an arrest… When it came to property crimes, the number was 0.1 percent.” When our car was broken into and my wife’s purse stolen, we had video of the perpetrator’s car, video of the perpetrators, and traced my wife’s stolen cell phone to an apartment. We gave all this to the police, including the address where they could immediately recover the stolen goods, but they refused to send an officer to do so.

These failures happen when bad ideas peddled by professors leave the campus and infect society. Instead of proven ideas to create a safe and fair society that allow for human and animal flourishing, they reflect destructive, racist, pessimistic delusions based on identity politics and a willful misinterpretation not only of the past and present but the potential for our collective future. In Montford’s case, it’s “Restorative Justice,” which includes defunding the police and abolishing punishment and prisons since crime is “believed” to be the product of capitalism, while notions of personal responsibility are deemed racist.

When over 500 of my neighbors packed a room with officials to demand Oakland respond to rising crime, one older woman talked of being robbed of her purse and being beaten by a group of young men: “They pulled me down on the ground, punching, kicking, dragging me through the street.” The Chief of the Oakland Department of Violence Prevention responded that the men who did that to her must be in a lot of pain and need our compassion. Mind-boggling. If anyone was in pain and in need of compassion and protection, it was the woman who was beaten. Five hundred people rightly booed him.

Yet, equally mind-boggling, my neighbors — the same voters who ousted the Mayor and District Attorney because of rising crime, failures by the police to investigate and solve those crimes, and reductions in punishment for those who do get arrested based on fringe “restorative justice” ideas peddled by post-modern academics — voted in a city council candidate who ran on a “defund the police” platform. In Oakland, my neighbors want lower crime but also want to cling to their fantastical ideologies. Like Montford, they can’t have it both ways.

Since crime and enforcement are inversely proportional to one another — the greater the enforcement, the lower the crime and vice-versa — if we don’t want the crime, we need to vote accordingly. It is simple cause and effect. As humans, we have choices.

Animals are not so lucky.

Montford erroneously claimed the case was in Ohio.

Dear Nathan, l as a former School Principal and Professor of Education absolutely agree with your wise critique of academia. We need to advocate for love and kindness to all the loving animals who as sentient beings deserve to be treated with Compassion just as humans should be treated. It is hard to fathom how any human being can be blind to this need for love and compassion.

Short video and shout out from Fenix the dog with cerebellar hypoplasia

https://www.facebook.com/reel/1760104714736169

What is shocking is the inborn stereotyped prejudice demonstrated by egotistical academics who assume Blacks, Hispanics and Asians don’t share the same universal values all human beings share, ones we witness every day: compassion and kindness towards all animal life. They should stop rationalizing and using their prejudice for a buck and a publication.