Follow the (Lack of) Money

Earlier this month, I published a review of The Lives and Deaths of Shelter Animals, a book by Katja Guenther. The book (incorrectly) claimed that dogs are being killed because of white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalist exploitation.

I argued that a lack of basic sheltering programs — not lack of diversity — explained shelter killing. I argued that her premise threatened to derail No Kill progress by diverting the attention of the animal protection movement away from proven strategies towards social theories about race that are not only wrong, but bear little relevance to shelter killing. And I rejected the author’s depiction of minorities as exploitative caretakers as factually inaccurate and racist.

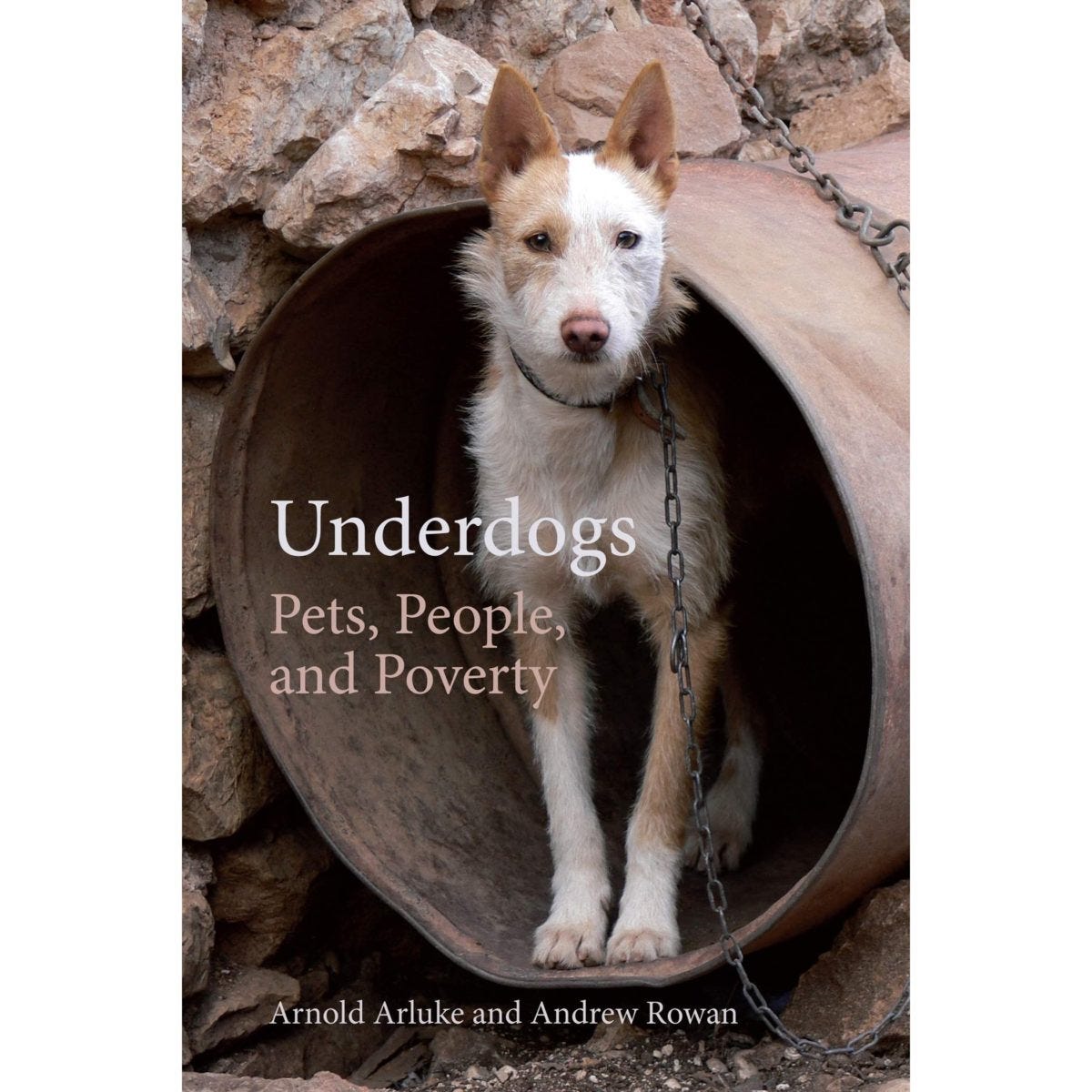

Now, another new book argues that race explains treatment of animals outside the shelter, too. In Underdogs, Andrew Rowan and Arnold Arluke claim that we need to develop “ethnoracial cultural sensitivity” when it comes to judging how poor people of color treat their animal companions. Rowan and Arluke claim that they have “culturally specific” “folk knowledge” that underscores their “indigenous” human-animal relations. And they argue that shelter workers should lower their standards in deference to this folk knowledge, even when doing so is “at odds with the humane society’s own core beliefs about how animals should be cared for,” such as agreeing to vaccinate the dogs of dogfighters (rather than rescuing the dogs and having the perpetrators arrested and prosecuted). Doing so is necessary, they argue, because medical care, affection, and treating animals as family members are “middle class” and “White” values, rather than objectively better ways because they reduce suffering and maximize happiness.

Like Guenther before them, Rowan and Arluke are confusing cruelty with “culture.” Like Guenther before them, they are making unfounded claims that infantilize people of color. And like Guenther, they embrace these conclusions, despite evidence given in their book that clearly points to the contrary. As they themselves conclude, “When cost and transport barriers are removed, low-income black and Hispanic pet owners behave no differently than do white owners…” And yet, they argue that somehow (poor) Black people are fundamentally different from (middle class) White people with respect to animal care. Once again, these conclusions threaten to derail progress for animals by inaccurately portraying animal protection as a tool of racial oppression.

There are right and wrong ways of relating to animals

Rowan and Arluke, for example, note that, “Dogfighting is strongly opposed by the shelter because dogs are tortured, are disposed of when no longer good fighters, suffer from wounds that go untreated, [and] are bred to be used as bait…” They also note that, “Dogfighters who breed dogs are not interested in sterilizing their puppies.” Given the impasse, the authors wrongly suggest that the former should compromise, rather than the latter be prosecuted. Specifically, “As [shelter] workers try to transcend their objection to these practices by focusing on the bigger picture of promoting animal welfare, they develop strategies to work with… dogfighters so they vaccinate and sterilize at least some of their animals.” By this tortured logic, Rowan and Arluke seem to suggest that ensuring that dogs destined to be ripped to shreds be vaccinated is a greater priority that ensuring that animal cruelty laws be enforced so that those dogs do not become victims of dogfighting.

According to the authors, not only should we look the other way at intentional harm to animals, but we should likewise be willing to suspend disbelief, such as equating after-the-fact rationalizations for neglect or cruelty like not regularly feeding an animal with race and culture. Rowan and Arluke claim, for example, that some Black people, “believe that the best way to stop a chained dog from knocking over its food bowl is not to feed it.”

Some ways of relating to animals are better than others. Determining which does not start with the skin color of the person the animal is connected to, but objective norms rooted in the animal’s biology and Enlightenment values, including the unalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Feeding a dog daily is better than feeding a dog two times per week. Letting a dog sleep in the house is better than chaining the dog outside 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Providing professional veterinary care is better than untested “folk” remedies. And treating dogs tenderly is better than fighting a dog to see if he can kill the other. These are not “middle class” behaviors and they are certainly not “White” values; they are ways of relating to animals that objectively increase the well-being of dogs and cats, and therefore, should be afforded to all of them, irrespective of the ethnicity, gender, race, or class of the human with whom they live.

There are, of course, more effective or less effective ways of changing behavior so as not to make those who engage in it defensive, causing them to reject advice or support for the dog, like free fencing to get dogs off chains and quality food to get cats and dogs better nutrition. Aside from dog fighting which should always lead to rescue/seizure, arrest, and prosecution, we want the other behaviors to change, through education if possible, but prosecution if necessary because the welfare of animals is of consequence. But regardless of how we go about it, we need not pretend those who do not feed their dogs so they don’t have to clean up the mess aren’t being intentionally cruel. Nor should we allow the authors to pretend otherwise by claiming that this is a unique “ethnoracial” practice.

In fact, many, if not all, of their similar claims turn out not to be nothing more than commonplace manifestations of basic human nature. For example, they claim that Black people rely on “folk knowledge” or “indigenous” ways of caring for animals, such as trusting the opinions of friends, family, and neighbors over professional “experts” or relying on such individuals for assistance at the loss of housing or transportation; behaviors that are hardly culturally specific. Wealthy and White people likewise tend to trust their social peers and are more likely to believe what they read on social media than professional news sources. They are also likely to rely on friends and family for assistance when needed. Of course, people with means can rent a car, rather than rely on a friend for a ride, or afford to board their dog, rather than asking family to take him in, but fundamentally, the behaviors are similar. This is hardly surprising. Love of dogs and cats, regardless of race or income, is near universal. What is distinct is what happens if families do not have the resources to provide for veterinary care when their dogs and cats need it.

Although Rowan and Arluke appear to have wanted to write a book about the impact of race and pets, they have actually written an important book on the impact of class. They also appear to have wanted to write a book that cited skin color as a reason to condone differential levels of care, only to discover that people of color have the same views as everyone else.

Stripping away the racist distractions, their compiled evidence shows that there are three primary barriers to better care that stand in the way of lifting animals out of want and allowing poor people to act like the kind of pet owners they want to be: cost (and transportation), the regressive practices of private practice veterinarians and their industry associations, and the equally regressive practices of animal control agencies and their regressive enforcement officers.

Cost is a barrier to better care

Without access to free and low-cost medical programs, eight out of 10 pets in the poorest neighborhoods of West Charlotte, North Carolina, never see a veterinarian. Nonetheless, Rowan and Arluke rightfully argue that this doesn’t mean people on the lowest rungs of the economic ladder don’t care about their animals. To the contrary, the authors admit that, “Attachments to pets… can be as profound and lasting as among pet-owning residents in any neighborhood” but “Low-income pet owners or those living in poverty have fewer resources to express or act on their attachment.”

For example, the authors highlight the touching story of one woman who “grieved over her recently deceased 14-year-old cat but never had a photograph taken of ‘Chloe.’ So she scoured magazines to find a likeness of her cat and found one that she framed and hung in her living room.”

Moreover, Rowan and Arluke note that after implementation of a free spay/neuter program in “the most poverty-stricken” neighborhoods, where the majority of residents are Black, 80-90% sterilized their animals. Similar numbers were achieved for other medical care, such as vaccinations.

Even Rowan and Arluke concede that, “class may have more influence on these human-animal relationships than race or ethnicity.” The end result is an unsurprising and mundane conclusion: the less money people have, the less they can spend on veterinary services. Consequently, if cost is removed as a barrier, the vast majority avail themselves and their pets of it. Specifically, the data shows that the vast majority of “individuals living in or near poverty do their best to care for their animals, given severely limited resources, adverse conditions, and unpredictable crises that constantly test their ability to have a residence to live in, food to survive, utilities for comfort and health, and medical care for all members of the family, whether human or animal. In other words, the level of care they provide reflects not their intent but the structural limitations of living in or near poverty.” Follow the lack of money.

For the small percentage of poor people who do not initially get the free care offered for their pets (about 10%), Rowan and Arluke speculate that the state’s history with eugenics that forced black women to get sterilized is to blame. The evidence for this proposition is weak, with the authors admitting that it is “rare for pet owners to directly refer to the state’s forced sterilization of humans as the reason why they do not want to sterilize their animals.” Instead, the evidence suggests their hesitancy lies with a more pedestrian, though ubiquitous, tenet of human nature: embarrassment. Poor people do not want to be judged as needing a free hand out or deemed irresponsible. By offering the services in a non-judgmental way and, for those who can afford it, requiring a small co-pay, the stigma is lifted overcoming their hesitancy. Many of these individuals will then even subsequently act as “ambassadors” encouraging others in their social circles to use the services, resulting in “a flurry of calls requesting sterilization.” This conclusion is neither surprising, nor novel.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic propelled “the poverty rate into double digits,” a 2018 study found that roughly one in four pet households had difficulty getting needed veterinary care because of its high cost. This not only impacted the quality of life (and in cases where they could not afford emergency care, the actual life) of the animal, it also negatively impacted the emotional health of the people.

That same study noted that the old saw, “if you can’t afford a pet, you shouldn’t have one,” was not only oversimplified given the broad demographics of the families involved (for example, “there are also middle-class families that live paycheck to paycheck, with limited funds for veterinary care, especially when the need involves high-cost”), it was counterproductive (it does nothing to solve the problem), unfair to people of limited means, and also unfair to animals in those homes. It concluded that it would lead to more death as “29 million dogs and cats live in families that participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as food stamps.” Like the evidence presented in Underdogs, the study concluded that there “is a need for a financial support system for accessing veterinary care that opens the door for more families to receive it.” In short, poor people “want to be responsible but face barriers; however, with the help of affordable veterinary care programs, they can care for the animals in ways they would like to.”

Private practice veterinarians and their regressive veterinary associations are barriers to better care

The problem is that private practice veterinarians and their associations are suspicious of pro bono veterinary services and stand in the way of their implementation. As I noted in my 2008 book Redemption, the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) has a long history, going back to the 1970s, of opposing municipal or SPCA-administered spay/neuter clinics that provided the poor an alternative to the prohibitively high prices charged by some private practice veterinarians. Despite the fact that low-cost spay/neuter services aimed at lower income people with pets had a well documented rate of success in getting more animals altered and reducing the numbers of animals surrendered to and killed by “shelters,” the AVMA would not agree to any program that they perceived threatened the profits of veterinarians, even though poor people were not, and were unlikely to ever be, their customers. In 1986, the AVMA also asked Congress to impose taxes on not-for-profits for providing spay/neuter surgeries and vaccination of animals at humane society operated clinics in order to discourage them. And to this day, aside from spay/neuter and vaccinations, veterinary associations generally prevent shelters from offering needed veterinary services to people who could not otherwise afford it and will sue, or threaten to sue, non-profit organizations that try. Rowan and Arluke note that, “The Alabama Veterinary Medical Association recently tried to pass a law banning shelters from offering veterinary services” and its North Carolina counterpart was considering similar legislation.

Animal control agencies and their regressive enforcement officers are barriers to better care

Unfortunately, private practice veterinarians are not alone in acting as a roadblock to improving the lives of the pets of the poor. Municipal pounds do, too. Rowan and Arluke cite studies that show that people living in neighborhoods with high rates of poverty are “more likely to befriend stray or feral animals of unknown origin by occasionally feeding them or briefly letting them into their homes” and “consider to be unproblematic community pets or tolerate as just part of the neighborhood landscape.” This finding mirrors those of Professor Alan Beck whose book about community dogs in Baltimore, Maryland, published almost 30 years earlier, found neighborhood dogs adopted into homes from the streets of low-income neighborhoods tended not to gain much weight as they were already getting enough to eat from handouts. Beck also found that community animals impounded by the shelter were often reclaimed and released back to the neighborhood by local residents who considered them “pets of the block.”

In contrast to how residents view these animals, Rowan, Arluke, and Beck all found that, “animal control officers see them as nuisances to be disposed of, even though local residents have not filed a complaint with the department and consider them to be shared community pets.” This not only sets up residents in an antagonistic relationship with animal services to the detriment of animals, but the problem is exacerbated because of the prohibitively high fees now charged by regressive pounds that prevent poor families from reclaiming either their own pets or community pets of the block, resulting in higher rates of killing.

Where should we go from here?

The evidence presented by Rowan and Arluke does not compel us to accept “traditional identity,” “folk…” and “indigenous” ways of relating to animals by developing “ethnoracial cultural competence.” Instead it compels us to:

Change the law to allow pro bono veterinary services, despite objections from regressive private practice veterinarians and their industry associations;

Subsidize the cost of (and transportation to) that care as the vast majority of poor people (roughly 80%) will get it if those barriers are removed;

Provide that care in a non-judgmental way and for those with some means, require a small co-pay in order to win over the small percentage of poor people (roughly 10%) who are embarrassed by what they perceive negatively as a “hand out” and are reluctant to use free services for fear of being judged irresponsible. Doing so will not only increase the number of people who get veterinary care for their animals, it will turn them into “ambassadors” that encourage others in their neighborhood to do the same;

End the round up and killing of community cats and dogs by animal control officers since no one asked them to (and, even if they did, they shouldn’t); and,

Eliminate barriers to animals being reclaimed from shelters if they end up there, such as high impound fees.

To these five prescriptions, I would add a sixth: End housing discrimination for people with animal companions, since the majority of the poor rent, rather than own. Even before the pandemic, a study found that one in four renters lost their home because of a restriction on housing. In addition to protecting animals already in those homes, doing so would also allow almost nine million more animals to find new homes, roughly eight years worth of killing in U.S. pounds.

In short, we just need to treat people like people by offering “Low or no-cost sterilization, vaccination, pet food, fences, and [veterinary…] treatment.” Doing so will “go a long way towards changing the quality of life for dogs and cats and the people who want to care for them.”

For the remaining few who fight dogs, serially breed dogs, chain dogs 24/7, refuse to provide veterinary care despite that it is freely available, or don’t feed their dogs, criminal prosecution (and rescuing the pets) is both necessary and proper, regardless of the color of the abuser’s skin. Otherwise, we will have subordinated the rights of animals to the interests of those who harm them, undermining the central tenet of the animal protection movement and leaving animals in harm’s way. That is something we should never do.