The Animal Welfare Act fails most animals

News and headlines for February 25 - March 4, 2023

These are some of the stories making headlines in animal protection:

Legislation pending in California would require shelters to notify rescuers 72 hours before killing an animal. AB 595 was named after Bowie, a shy 12-week-old puppy killed by a municipal shelter, despite a rescue group willing to accept him into their foster care and adoption program.

The No Kill Advocacy Center is asking Californians to please contact members of the Assembly Committee hearing the bill and urge them to vote YES on AB 595 (Bowie’s Law).

A Maine legislator is trying to criminalize allowing cats to go outdoors, claiming that doing so is necessary to protect birds. Not only will this result in the round-up and killing of cats, but people could also be fined as much as $500.

As previously reported, the notion that cats impact bird populations in the continental U.S. has been thoroughly debunked. In a recent article, I also made the case that when self-proclaimed “conservationists” call for killing cats, they are not motivated by saving birds. Instead, they are motivated by a hatred of cats, as killing cats is sadistic, unscientific, hypocritical, and unworkable. A recent study also found that lethal methods harm caregivers, leading to grief, trauma, poor physical health, and long-term psychological distress, including profound guilt, loss, and inability to eat.

Thankfully, the bill is running into heated opposition.

While Austin Pets Alive (APA) falsely claims that Austin is a No Kill community, APA and the city pound continue to turn their backs on Austin animals, including lost animals and those needing new homes. As previously reported, “incompetence and uncaring at Austin Pets Alive and the city’s shelter are responsible for a crisis with lethal consequences for the animals.”

Now comes news that despite thousands of fewer intakes, the city pound is still refusing to take in lost dogs despite being one of the best-funded shelter systems in the nation. Instead, pound staff tells finders that if they cannot handle it themselves, to leave the animals on the street or re-release them on the road. The pound’s director tried to justify the policy by pointing out that while 2022 saw thousands of fewer intakes, it also saw roughly 1,000 fewer adoptions. This is his own fault. For most of the year, he closed the shelter for adoptions on Sundays. The number of typical adoptions on a Sunday is roughly the difference in the lower number of animals adopted.

In addition, another report this week found that the city is no longer efficiently sterilizing animals, causing concern about an influx of pregnant animals. Austin was “spaying and neutering 10,000 to 11,000 animals annually... That dropped to 5,900 in 2020, 4,900 in 2021, and 4,700 in 2022. It is not acceptable that it’s taking nine months to get a large female dog spayed…”

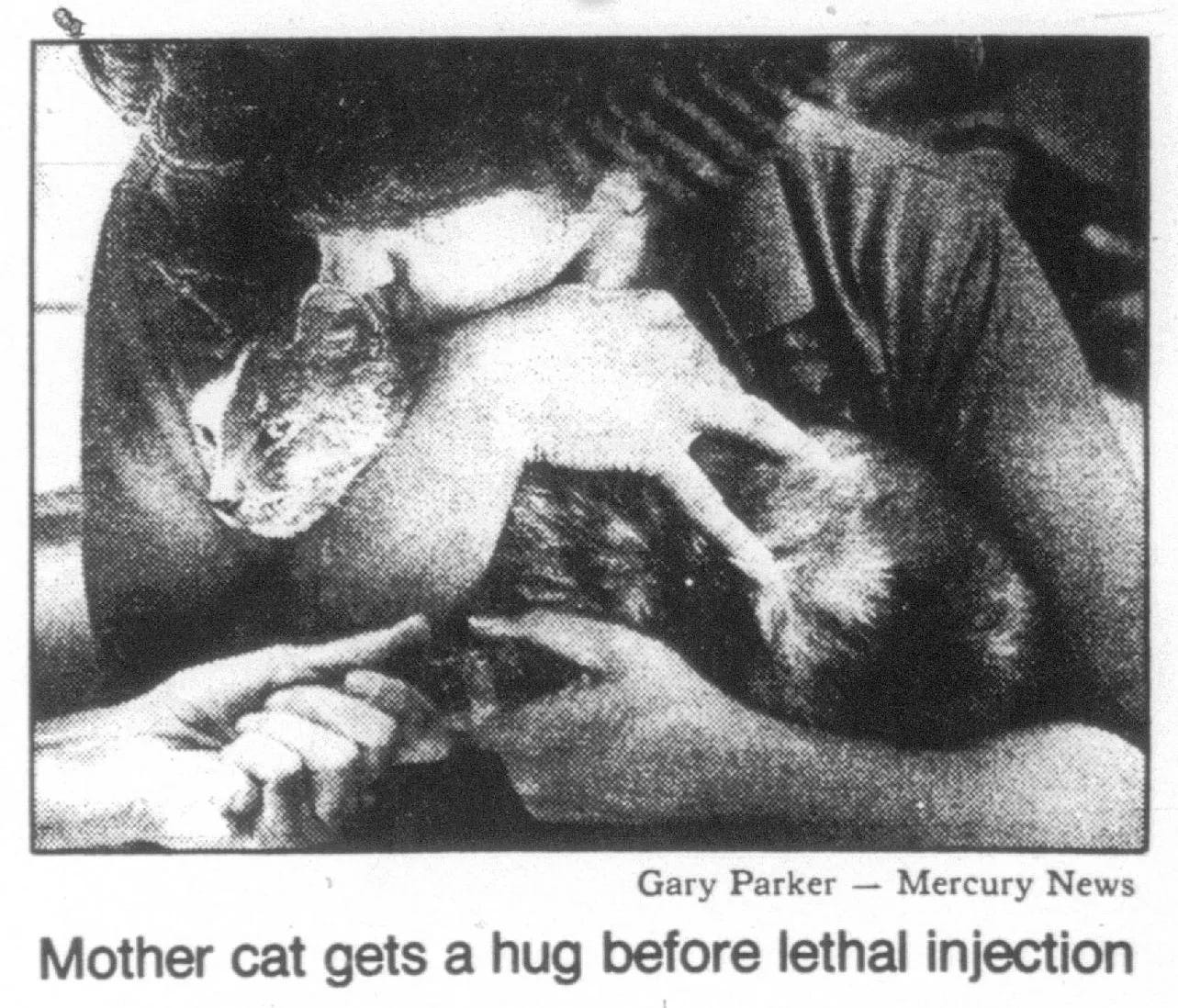

On October 25, 1990, reporters from across the nation converged upon a small room at the Peninsula Humane Society in San Mateo, CA, run by Kim Sturla, and she had their full and rapt attention. While “cameras clicked and onlookers gasped,” Sturla took “a tan-and-gray calico cat and her four tiger-striped kittens” — all healthy, adoptable animals — “and injected them in the stomach with poison from a bottle marked ‘Fatal Plus.’” One by one, their tiny bodies went limp, and they slumped to the table. By the time she had finished, Sturla had killed eight animals, five cats and three dogs, on television. Dubbed a “public execution,” the first-of-its-kind public relations ploy was an instant sensation.

“The Status Revolution,” a new book by Chuck Thompson, claims that by doing so, Sturla increased the status of rescued animals and launched the No Kill revolution in America. That makes no sense. You cannot kill your way to No Kill. And killing animals does not bestow status on them. It degrades them. To increase their status, one must show they matter by fighting for them and their right to live. While the credit for both belongs to someone else, Sturla leaves behind a legacy of failure, rejected ideas, and a horrific body count of animals for whom she showed a lifetime of disdain for their safety, well-being, and rights.

Little wonder, The New York Times called the explanations given for trends in the book “scattershot” and “off the rails.” The conclusions in the chapter discussing dogs are even worse.

The pit bull ban in Miami-Dade County will end if legislation working its way through the Florida state legislature is passed and signed into law. SB 942/HB 941 would prohibit cities from targeting specific “breeds” for extermination.