Regarding Henry

As reported last week, Kristen Hassen and Katja Guenther wrote a journal article that calls for abolishing animal shelters and leaving the welfare of dogs and cats to whatever fate befalls them on the streets.

My rebuttal to their cruel suggestion is here.

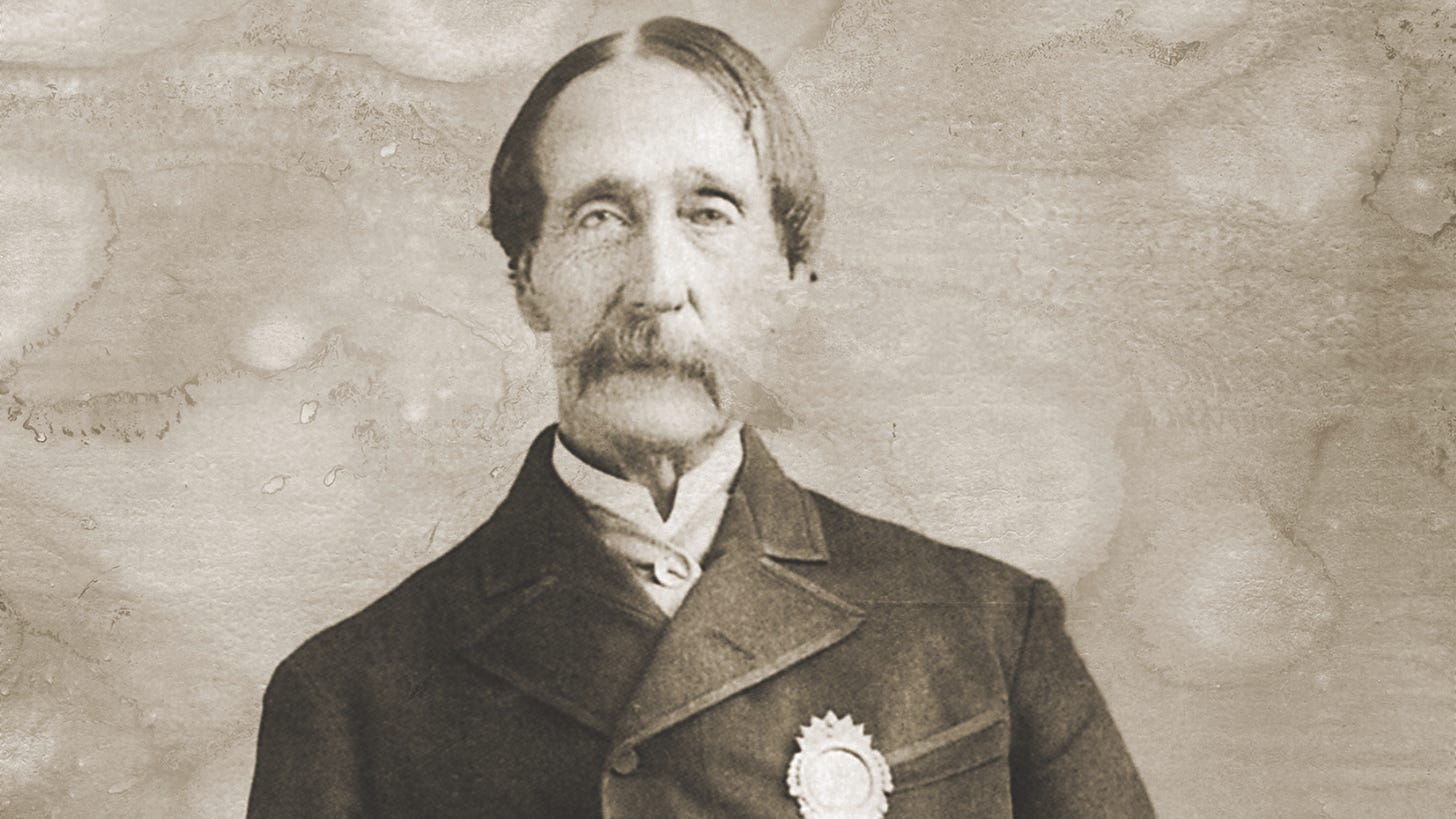

To make their case, Hassen and Guenther offer a revisionist history of the humane movement. Specifically, they argue that 19th-century reformers — like Henry Bergh, Caroline White, and George Angell — were racist capitalists intent on doing the bidding of bankers and financiers by oppressing black people and other “marginalized communities.” Bergh founded the nation’s first Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in New York, White founded the second in Pennsylvania, and Angell founded the third, the Massachusetts SPCA (MSPCA).

Because Hassen and Guenther lack a language for progress, they claim — without evidence — that all organizations revert to their founding missions. Not only is this unduly pessimistic, but the claim that reformers like Bergh, White, and Angell were racists serving the moneyed classes is untrue.

On top of ignoring that many early humane activists were black, both White and Angell were abolitionists. Indeed, Angell was an attorney “who defended many of the formerly enslaved arriving in Boston via the Underground Railroad.” (Wasik, B., “Our Kindred Creatures,” p. 10 (2024).) In a speech commemorating the first anniversary of the MSPCA, Angell celebrated,

The suppression of the slave trade. The abolition of slavery. The growth of free government. The elevation of labor. The coming-up of woman towards equal rights with man.

He saw protections for animals as the next logical step.

Meanwhile, Bergh — whose father was the first shipbuilder in the United States to hire black people and paid all his workers equal wages for equal work — fought bankers and financiers who owned horse railways. He fought wealthy sportsmen by trying to ban hunting. He sought to remove animals from the capitalist economy by banning their exploitation in other contexts. He defended poor children by creating the first Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. He also arrested and prosecuted corrupt dog catchers.

To those who have seen Redemption, my documentary film about the No Kill revolution in America, or read the book on which it is based, Henry Bergh needs no introduction. To those who haven’t, after Bergh succeeded in getting New York State to pass an anti-cruelty law, he put a copy in his pocket and took to the streets that very night — and every single night after that for the remainder of his life — to help animals.

The annals of the day describe what happened next:

The driver of a cart laden with coal is whipping his horse. Passersby on the New York City street stop to gawk not so much at the weak, emaciated equine, but at the tall man, elegant in top hat and spats, who is explaining to the driver that it is now against the law to beat one’s animal. Thus, America first encounters ‘The Great Meddler.’

And meddle he did. “Day after day,” he wrote,

I am in slaughterhouses; or lying in wait at midnight with a squad of police near some dog pit; through the filthy markets and about the rotten docks; out into the crowded and dangerous streets; lifting a fallen horse to his feet, or perhaps sending the driver before a magistrate, penetrating dark and unwholesome buildings where I inspect collars and saddles for raw flesh; then lecturing in public schools to children, and again to adult Societies. Thus my whole life is spent.

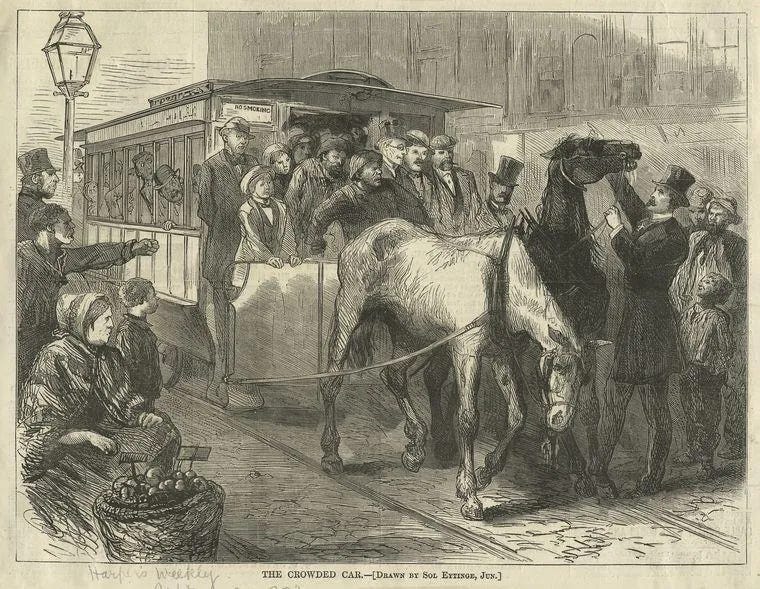

Notably, Bergh approached a situation by assuming the best in people and allowing them to rise to his expectation of their decency. He understood that people wanted to think of themselves as good and leveraged this to the animals’ advantage. During rush hour traffic in crowded Manhattan, when he came across horses with bleeding noses, straining to pull a trolley filled beyond capacity, he would stop the car dead on its tracks and loudly announce, “All good Christians, disembark!” People who wanted to identify as moral would willingly exit the train.

While his act of stopping the trolley and telling people to get off inherently implicated them in the abuse he was trying to end, he allowed people to save face. And he allowed them to choose to be a part of the solution so they could own that act of compassion, wear it with pride, and hopefully do better next time, even when he wasn’t around to request it.

While Bergh’s ASPCA is primarily remembered for its efforts to protect dogs and horses, he actually worked to protect all animals. Every time he was told he was going too far — as when he attempted to ban the shooting of pigeons, the killing of rats, or to get a law passed banning laboratory and medical school experiments on animals — Bergh was undeterred:

Almighty God… entertains no discriminating partiality for any of His creatures but His affection is extended to all alike…

The insect in the plant, the moth which spends its brief hours of existence in hovering about the candle’s flame, nay, the life which inhabits a drop of water, is as much an object of his special Providence as the mightiest monarch on his throne.

Admittedly, Bergh had his blind spots. Unlike Caroline White, for example, he was not a vegetarian. But there is no denying that Bergh was also well ahead of his time and a true visionary regarding animals. He even foresaw the potential for corruption within the organization he founded, once writing that,

The chief obstacle to success of movements like this [is] that they almost invariably gravitate into questions of money or politics. Such questions are repudiated here completely: If I were paid a large salary: I should lose that enthusiasm which has been my strength and my safeguard.

Indeed, when Henry Bergh founded the ASPCA, he fitted it with what he called “the very plainest kind” of furniture. When the Governor of New York visited the organization, he stumbled over a hole in the old carpet. He said: “Mr. Bergh, buy yourself a better carpet and send the bill to me.” To which Bergh replied, “No, thank you, Governor. But send me the money, and I will put it to better use for the animals.”

Although Hassen and Guenther may slander Bergh — and other reformers like White and Angell — to make a name for themselves, his contemporaries knew the kind of person he was. The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote of him:

Among the noblest of the land;

Though he may count himself the least;

That man I honor and revere;

Who, without favor, without fear;

In the great city dares to stand;

The friend of every friendless beast.

And he was.

Although Bergh, White, and Angell are not well-known, we and the animals greatly owe them. Every humane society that stands up for animals, every animal protection group that gives voice to the voiceless, and the millions of animals who have been saved thanks to the efforts of activists and rescuers are a legacy to their lives. Bergh and his contemporaries were some of the first Americans to weave the ideals of animal protection into our jurisprudence, the American psyche, and the fabric of American life.

Thank you for your relentless and tireless pursuit of justice for all that live among us, tiny and winged, or large four and two legged. I don’t know why the world is so switched around so that needless killing of animals is called “preserving public safety” when humane options will do, or killing is called “bringing peace” to a distressed animal when one should just relieve the distress. Or calling for the disbandment of sheltering animals “freedom” leaving them in harm’s way. Re-naming cruelty and hiding it behind lofty language doesn’t change the reality of facts..

Something has gone very wrong with this society when all that matters is clicks for ego and the cost is borne by animals or in the case of politics when anyone disadvantaged becomes fair game. Taking down heroes just to get one’s name out in public is vandalism, graffiti on the wall of truth.

There are so many rescue groups and individuals jumping in to help animals that I think the people that we disagree with are just best left while we go about our business helping animals by forming and reforming working groups to get work done.

It is best to just find people we like working with and do the work that needs to be done.