Believe

Dear friends,

To love animals and be acquainted with the many ways in which they are killed or otherwise harmed in our culture is painful, leading to feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and anger at one’s fellow humans. I, too, struggled with these emotions for many years, often to the point of misanthropy. But my views have changed over time, and my despair at people replaced with faith in them.

Given the many comments I receive that reveal many of you likewise struggle because of your love for animals, I am sharing why I remain optimistic for the future. And, perhaps most importantly, why I believe such optimism is essential for our success. I hope this not only gives you comfort but inspires in you the same dedication and determination that it inspires in me.

Nathan

For decades, the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), the ASPCA, PETA, and local shelters have schooled us in the belief that the American public is irresponsible and uncaring, both by allowing the birth of “unwanted” dogs and cats and by abandoning animals in shelters in epidemic numbers.

When many of us began questioning shelter killing at the dawn of the No Kill movement, we were given a narrative that placed the blame for it squarely on the shoulders of a callous American public. But was it true then? And is it true now? Although I no longer believe so, there was a time when I would not have hesitated to answer that question with an emphatic yes!

In the early 1990s, I was a young law school student at Stanford University, fighting animal abuse on many fronts with the Stanford Animal Protection and Education Society, the student group I founded.

I opposed keeping animals in captivity by doing educational leafleting in front of zoos and aquariums. I encouraged others to adopt a more humane diet by distributing information about veganism. I fought animal research by exposing the cruel experiments and poor conditions animals were forced to endure on the Stanford campus. I even rescued and found homes for former research animals. And with the Palo Alto Humane Society, Stanford Cat Network, and, later, the San Francisco SPCA Law and Advocacy Department when that organization was (though no longer is) the leading voice in the No Kill movement, I worked to promote an end to shelter killing.

Working to overcome the abuse of animals on so many fronts, I believed the world to be a cruel, dark place filled with cruel, dark people. I was not alone. During my second year of law school, I met my future wife, Jennifer, when we both joined a grassroots organization to defeat legislation introduced in California at the behest of the Fund for Animals (an organization that eventually merged with HSUS). AB 302 and AB 1000 not only called for the round-up and killing of cats — by making it illegal to trap cats except for “proper disposal” as if they were nothing more than yesterday’s trash — they would have authorized animal control officers to immediately kill cats in the field.

Jennifer had already worked for several animal protection organizations and spent most of her free time on animal advocacy and rescue. Like me, she was happy to have met a kindred spirit — another person who shared her love and concern for animals, a quality that traditional animal protection movement dogma had taught us both to believe was in tragically short supply. So while we complemented each other’s strengths, we also unfortunately fed each other’s disdain for the public.

Shoot First, Ask Questions Later

When we noticed that a local photography studio that left spotlights on the photographs in the window also put a spotlight on their pet bird every night, we were reminded of the cruelty of factory farms where constant lighting stresses birds to the point of illness. In response, Jennifer sent an angry letter to the studio owner, asserting that birds were not artwork to be put on display and condemning him for jeopardizing the bird’s health and well-being.

When we found a skinny, sickly, stray dog wandering the streets, we decided not to return him to his family, certain that his poor health resulted from neglect and abuse. And after news of my rescue of a tiny, terrified kitten who had become trapped inside an abandoned bank vault became a media sensation and offers of adoption came pouring in, we recalled the cruel building superintendent who had determined to let the kitten die, surmised that no one could be trusted, and adopted him ourselves.

While trying to make the world a better place for animals was gratifying, being immersed in work designed to combat animal abuse constantly reminded us of it. Living in the trenches, we became myopic, believing that most people didn’t care about animals or their suffering. Suspicious of everyone and always anticipating the worst, we became blind to any evidence that countered those expectations.

When the owner of the photography studio, graciously ignoring the hostile tone of Jennifer’s letter, wrote her a thank you note for letting him know that the spotlight was harmful to the bird, assuring us he dearly loved Tony and promising to keep the light off so Tony could sleep, it should have made an impression.

When we began to see “missing dog” signs for the stray we had found, and a fellow rescuer informed us that the dog was suffering from cancer and his heartsick, worried family desperately wanted him back, we returned the dog but ignored the lesson.

When the media got wind of my kitten rescue, and three television networks showed up at our door to tell his story on the evening news, we downplayed the concern and gratitude expressed by everyone who heard the kitten’s tragic tale.

Our glass was half empty, and we took what should have been cause for rejoicing and turned their meaning upside down. Admittedly, our suspicion often bordered on the absurd. Whenever we drove by empty boxes on the side of the road, we always doubled back to peer inside, worried they might contain an abandoned litter of kittens. And when we saw dogs in cars, we feared they were on the way to the pound rather than what was the far more likely explanation — they were out for a ride with a family who enjoyed their company. But then, thankfully, we woke up. And when we moved to Ithaca, New York, so I could take over and transform that community’s animal shelter, the blinders came off completely.

An Army of Compassion

Before we arrived, the shelter in Tompkins County was typical of most in the country: it had a poor public image, killed many animals, and blamed the community for doing so. Once there, I announced my lifesaving goal and asked the community for help. The response was overwhelming. Many people adopted animals. Others fostered them. Still others walked dogs and socialized cats. Veterinarians offered their services pro bono. Business owners offered free products as incentives to adopt. I was not timid about asking for help, and most people were incredibly generous and eager to assist.

Overnight, by harnessing that compassion and changing how the shelter operated, Tompkins County, New York, became the first No Kill community in U.S. history, saving all healthy and treatable animals. It didn't matter if they were blind, old, traumatized, or missing limbs. It didn’t matter if they needed socialization, training, around-the-clock bottle-feeding, medicine, or lifesaving surgery. It didn’t matter if they were dogs, cats, rabbits, guinea pigs, hamsters, rats, chickens, pigs, horses, or the occasional cow. They were all guaranteed a home, and they all found one.

For us, one of the most amazing things about the experience was that the people of Ithaca didn’t need convincing that this was a good idea or a worthy goal (in fact, they had been clamoring for it for years). They were ready and willing to make it a reality as soon as we arrived. They just needed a shelter director committed to doing so. And the achievement became a source of community pride, with bumper stickers throughout the county proclaiming “The Safest Community for Homeless Animals in the U.S.”

The day before we arrived in Ithaca, the shelter was killing animals. The day I started my new job, the killing ended. During the night that straddled those two days, nothing changed in that community other than the potential that already existed was finally being harnessed to the animals’ benefit.

We lived in Tompkins County for several years before returning to California to start The No Kill Advocacy Center, a non-profit organization dedicated to spreading the No Kill Equation — the programs and services that made such success possible — to shelters nationwide. And everywhere it succeeds, it is because people in those communities overwhelmingly rise to the occasion. Why? As we finally came to realize, the animal protection movement had gotten it wrong.

Our experience in Tompkins County proved that the story of the animals entering shelters in this nation did not have to be a tragedy. Shelters could respond humanely and compassionately without resorting to killing. We also realized that the old excuse of rampant human irresponsibility was not true. Because to make that case, one had to ignore the bigger, more optimistic picture of the hundreds of millions of animals in homes across the country cared for by people who go to great lengths to ensure their happiness and well-being. In short, we learned that there was enough love and compassion for animals in every community to overcome the irresponsibility of the few.

This is not to say that there are no uncaring people in the world. Of course, there are. And just like any social welfare movement, the animal protection movement is likewise plagued with corrupt people who have so thoroughly bastardized the mission of humane organizations that they undermine the cause they theoretically exist to promote. But most people value animals. What may seem to us to be overwhelming “support” for a status quo that harms animals is, in reality, people acting in blind accordance with inherited traditions.

Humans are creatures of habit. Most of us go with the grain without ever taking the time to consider if the way of life we have inherited from our parents and grandparents is the right or ethical way to live. Out of habit, we continue exploiting animals in ways that should have been rendered cruel anachronisms. Yet history shows that, as a species, we are far from hopeless. It may take time and effort to vindicate ourselves, but in the end, when someone comes along who compels us to see things differently — to see the disconnect between our common shared values of empathy and compassion and how the world we have inherited works against those values — most of us rise to the occasion, and the rest are eventually forced to follow. But to realize that potential, we must first believe it is possible.

All Good Christians, Disembark!

In Redemption, the first of my many books, I told the story of Henry Bergh, the founder of the nation’s first SPCA. Bergh was an unlikely hero — a wealthy aristocrat in 19th Century New York who could have spent his time traveling Europe and attending lavish parties but instead spent his days and nights patrolling the streets of the Great City for animals in need of his protection. His foresight and dedication were remarkable, as was how he often approached his activism.

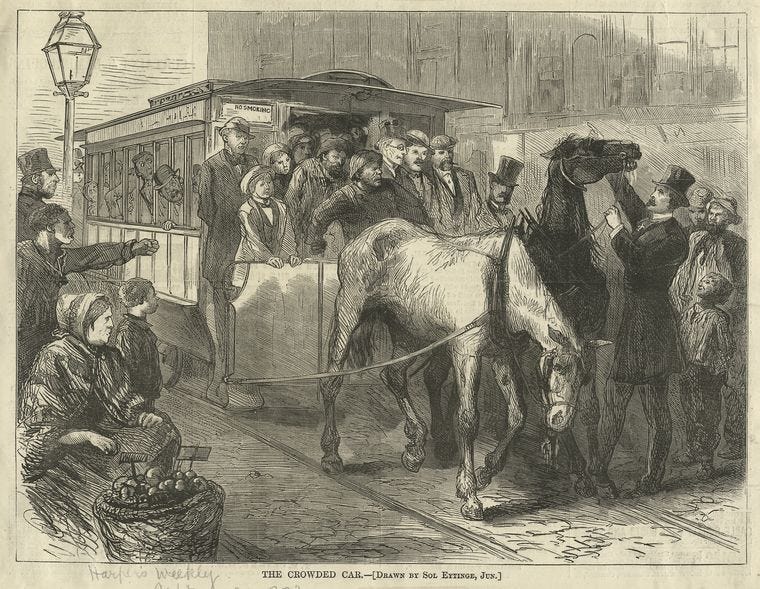

Although Bergh would do whatever it ultimately took to protect an animal from abuse — once pitching a trolley car driver in the snow for refusing to unload an overladen cart beyond a horse’s ability to pull — he always approached a situation by assuming the best of people, and by allowing them to rise to his expectation of their decency. He understood that people wanted to think of themselves as good, believed themselves to be good, and leveraged this to the animals’ advantage.

When, during rush hour traffic in crowded Manhattan, he would come across horses with bleeding noses, straining to pull a trolley filled beyond capacity, he would stop the rail car dead on its tracks and loudly announce, “All good Christians, disembark!” And many people, wanting to identify as just such a person, would willingly exit the train. While stopping the trolley and telling people to get off inherently implicated them in the abuse he was trying to end, he allowed people to save face. And he allowed them to be a part of the solution, so they could own that act of compassion, wear it with pride, and do better next time, even when he wasn’t around to request it.

Over 150 years ago, when animal abuse was rampant, and there was no animal protection movement in the U.S. but that which he and a few others were creating, Henry Bergh had the vision to believe in people and transform a nation. In 2022, in a society that has ended slavery and child labor, passed universal suffrage, created disability equal access, mandated civil rights, elected a black president, broke the glass ceiling, granted marriage equality, reduced shelter killing by 90%, and is on the verge of upending the factory farming system — the single greatest cause of human-induced suffering on the planet — in favor of cultivated meat, we have no excuse to give in to pessimism and defeatism. If we cannot see the immense potential offered by basic human decency and love of animals, then we will not attempt to leverage those things to protect them — to provide people the information that will help them make better choices, to create the products and services that make it possible to do so, to achieve a No Kill nation, and to grant them legal rights. As such, animals will continue to be harmed long past the point when we could have ended it.

What Would Henry Do?

After learning about Bergh’s approach, we began to emulate it in our interactions with people. We stopped assuming people didn’t care and gave them the benefit of the doubt. Seeing this approach work repeatedly, we came to understand that our job as animal activists was to help people understand how their actions undermine the inherent concern for animals they already have. We came to see that ignorance and not ill will account for so many harmful choices. When armed with the truth by someone who believes in them to do the right thing, many people will do just that and become the change we want to see in the world. Most importantly, we came to understand that misanthropy — as righteous and as justified as it may sometimes feel — harms rather than helps animals by blinding us to the potential for change.

There is a person who lives in my neighborhood whose dog used to bark wildly at other dogs on walks. When her dog did so, she would completely dominate the dog, holding the dog down, turning her over, and yelling at her. While my instinct was to confront her, she walked the dog often, and the dog was in good health, so — following Berg’s example — I assumed she was misinformed, not malicious. To allow her to save face, I sent an anonymous letter addressed to “Dog Loving Neighbor” and included a copy of the article, Heart-Wrenching Study Shows The Long-Term Effects of Yelling at Your Dog.

The study found that punishment (including yanking on the leash, scolding, yelling, shock collars, and restraint) hurts dogs. Compared to dogs trained by rewards, dogs trained using these aversive methods spent more time showing behaviors associated with pain and distress. They were more pessimistic and fearful. They also had higher cortisol levels — evidence of chronic stress — even if the punishment was relatively mild. I hoped she would take it to heart.

The first time I saw her after sending the letter, her dog was about to start barking as my dog and I walked by, and I prepared myself for a confrontation. But she responded calmly, getting her dog in a sitting position without yelling, yanking, or dominating. About a month later, I saw my neighbor and her dog again. As I walked by with my pup, she turned to her dog, and the dog quietly got into a sitting position. She gave the dog a treat and softly called her a “good girl.” All good Christians, disembark.

Admittedly, sometimes Jennifer and I still have to catch ourselves. Sometimes, old patterns of thinking are our knee-jerk reaction. One day, as we were searching under a BMW in a parking lot for an injured bird, the car owner arrived and asked us what we were doing. We said we were trying to rescue a crow dragging his wing. He looked confused, and we braced ourselves for his dismissal or a sarcastic laugh. Worse, we expected him to tell us to get away from his expensive car. But it never came. Instead, he began helping us, literally offering the shirt off his back to catch the crow.

It’s been 30 years since Jennifer and I first met and believed that no one cared as much as we did. How grateful we both are to have been proven wrong.

Reading this in a flood of tears. The positive expectations approach works for everything in so many ways. Love your work.

Wonderful article. I have learned so much from you. Thank you for all you do and share!